In this chapter, I focus on only one type of Russian Amazons, the oldest and originating type, warrior or fighting women. After reviewing and summarizing a variety of points of view, offered mainly in Russian sources but going back to the ancient Greek historiographer, Herodotus, on the phenomenon of warrior women (Amazons) in legend, antiquity, Russian history and folklore, I shall turn to the real-life stories (both told in the women’s own words) of two Russian women who, it seems to me, embody the Amazon model not as a manner of speaking, but as their way of being who they were. These two Russian Amazons are Nadezhda Durova, who is well-known in Russian and by now, Western culture, and Maria Botchkareva, who had passed into historical oblivion until the nineteen nineties, and is still hardly known outside a small circle of specialists. Finally, by comparing the ways in which Russian culture received the legacies of Durova and Botchkareva as well as the ways their culture perceived them and they perceived themselves, I hope to gain some insight into the shifting and often contradictory connotations of the name “Amazon” in Russian culture.

The legends about Amazons inhabiting the territories later settled by the East Slavs have their origin in the writings of the fifth century B.C.E. historiographer, Herodotus, who records the following story about the Scythians and the Amazons in his History:

Herodotus relates that after the battle with the Amazons, the Scythians realized that their enemies were women and decided to send them “about the same number of young men as there were Amazons,” not to do battle, but to mate with them: “The Scythians decided thusly because they desired to have children from the Amazons” (Herodotus, VI, 111). The Scythian youths and Amazons combined their camps, and the Scythians began to live with them as their wives. The Scythian husbands suggested moving back to their territory, but the Amazons refused: “We can not live with your women. Our customs are not the same as theirs” (Herodotus, IV, 114). In the end, the Scythians and their Amazon wives decided to settle in another locality. “They re-directed themselves through Tanais and then went to the East of Tanais for three days and three days to the north of Lake Meotid. Having reached the locality where they live to this day, they settled there” (Herodotus, IV, 116). Herodotus reports that the Sauromatians (a people ethnically related to the Scythians) originated from the Scythian-Amazon unions and retained the customs of the Amazons: “Sauromatian women…both with their husbands and on their own…go hunting on horseback, go on military campaigns and wear the same clothing as men.” A distant echo of Herodotus’ story about the Amazons, Scythians and Sauromatians can be heard in Russian folklore in the “Tale about the Kingdom of Maids and Men,” which was written down in 1891 by V.V. Bogdanov in the province of Smolensk (Kosven, 4).

In antiquity, the lives and customs of the Amazons and later, the Sauromatians as described by Herodotus provided a sharp (and some scholars have argued, intentional) contrast to the secluded, wholly domestic lifestyles of the majority of Greek women. The Amazons rode horseback, went to war and were victorious over enemies. Whether these warrior women of antiquity and pre-history were creatures of myth, or patriarchal propaganda created to scare Greek women into toeing the patriarchal line, or actually existed in fact is still a subject of controversy. However, in 1992–1995 a joint expedition of American and Russian archeologists, working in Pokrovka (120 kilometers to the south of Orenburg), did unearth a material culture that testifies to the existence of women warriors among the nomads who once inhabited these territories – Indo-Europeans who spoke an Indo-Iranian language. A clear analogy can be seen between this culture and what Herodotus wrote about the Amazons and Sauromatians. As the American archeologist, Davis-Kimball, who participated in the Pokrovka excavations, notes: “The material culture found in the Pokrovka burials is similar to that of the 6th–4th century B.C.E. Sauromatians and 4th–2nd century B.C.E. early Sarmatians documented in the Volga–Don interfluvial” (Davis-Kimball, 330). Many artifacts from the Pokrovka burials (14% of the female burials contained bronze and/or iron armaments), and from other sites in the Orenburg region indicate that “women warriors were found in some tribal units. … One of the most profound women warrior burials was that of a young female in Cemetery 2. To her burial she wore around her neck an amulet in the form of a small leather pouch which contained a bronze arrowhead. Along her right side an iron dagger had been placed and to her left her quiver holding more than 40 arrows, tipped with bronze, lay as it had been placed 2500 years ago” (Davis-Kimball, 336-337).

Additional information about Amazons who inhabited lands near or abutting Russian territory can be found in the writings of the ancient Greek geographer and historian Strabo (c. 63 B.C.E.–c. 21 C.E.) who locates Amazons in the Caucasus region. Unlike the majority of earlier commentators he does not describe the Amazons as wholly war-like, saying that for the most part, they spent their time pasturing herds, working the land and caring for their horses. The strongest of them engaged in hunting and sometimes, war. Strabo was also one of the first commentators to establish a connection between all-female (or Amazon) communities and island dwellers, an important linkage that may have facilitated the later conflation of Amazons with the 6th-century B.C.E. poet Sappho who lived on the island of Lesbos. Strabo wrote that in the ocean not far from the coast opposite the estuary of the Liger River, a small island was located on which lived a group of Samnite women who were worshippers of Dionysus. No man had ever set foot on this island, Strabo reports, but the women there did occasionally journey to the mainland in order to have sexual relations with their menfolk, after which they would return to their island.

Although Strabo expresses skepticism about whether Amazons really existed in the Caucasus, several late 19th-century Russian scholars and ethnographers engaged in a lively debate on this issue and argued that warrior women and all-female communities did once inhabit this area in antiquity. In “New Notes on the Ancient History of the Caucasus and its Inhabitants” (1866), the historian, I.I. Shopen, argued for the existence (in theory) of ancient warrior women on the basis of “historical necessity.” Shopen theorized that at times in prehistory when people in the Caucasus lived in conditions of lawlessness and fell easy prey to robbers and vandals, the entire male population of a given locality could have been completely exterminated, and then the women who survived because they had remained at home would have assumed power in the community. Then, Shopen concluded, the most bellicose of the women would have decided not to submit to male authority ever again and formed themselves into an all-female republic (Kosven, 3, 25-26). It is possible that Shopen was influenced by the work of the German historian Bachhofen, the originator of the theory of matriarchy as the socio-political system that preceded patriarchy.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Russian ethnographer M. Kovalevsky, who belonged to the generation of Russian scholars that succeeded Shopen’s, studied the laws and customs of the Caucasian peoples. His research led him to compare certain of the laws and customs he observed among the peoples in his study with traditional attributes of the legendary Amazons. On the basis of this cross-cultural comparison, Kovalevsky reached the conclusion that the Amazons of antiquity had existed in fact, but that some of the long-standing traditional beliefs about them were pure fantasy, such as their alleged custom of burning off their right breast to facilitate shooting from a bow. He thought that other habits and behaviors commonly attributed to the “legendary” Amazons constituted a pre-historic origin for the traditional customs of the Caucasian peoples he described in his works.

Finally, at the beginning of the twentieth century the historian of the Kuban Cossacks, F.A. Shcherbin, analyzing the testimony of the ancient authors, advanced the hypothesis that the Amazons of pre-history were most likely the foremothers of the indigenous population of the Kuban. Shcherbin theorized that the Amazon legends reflected human relations at an early stage of history when group marriage was common-place, women were completely independent from men and were able to organize themselves into military units and detachments for defense of their territory. At this stage of informal conjugal arrangements, as distinct from later forms of marriage, women had the possibility of being Amazons, i.e. independent from men and protectors of their own way of life and their female rights (Kosven, 3, 27). Though the studies of Shopen, Kovalevsky and Shcherbin were methodologically flawed and never went beyond the realm of the purely speculative, they nevertheless gave the idea of women warriors in the ancient world the kind of serious, “scientific” consideration that idea deserved, but rarely received from their 19th-century colleagues. The archeological finds at Pokrovka a century after their theories were published show that some of their speculation was not so wild as it might seem.

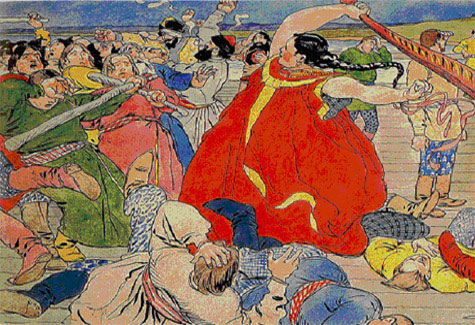

As is the case in most western European and Anglo-American cultures, so in Russian culture warrior women can be found in the folklore tradition as reflected in fairy tales and oral epics (the byliny). Popular notions of Amazons in Russian folklore are expressed in the images of the female epic heroes who are called polenitsy, polenichishchi, or polianitsy as well as in the fairy-tale figures of the Tsar-Maiden and the Warrior-Maiden. The very names of such virile virgins in Russian folklore convey the essence of their character and way of life. The polenitsy (literally, women of the fighting field) are women who fight or duel. The word in Russian for “duel,” poedinok, is one of the oldest meanings of the word for “field” (pole), attested in the thirteenth century. (Apropos, in the fifteenth-century Pskov Legal Code, the word “field” (pole) designates specifically, the place for the sentence of a legal duel to be carried out in order to resolve a suit involving two women; the sentence specifies, moreover, that the women are prohibited from using “hirelings” to fight for them—Dictionary of the Russian Language, XI–XVII centuries, vol. 16, pp. 205-06). A special verb, poliakovat’ (to be a woman of the field), is used in Russian oral epic poetry to describe the “fighting woman’s” or “female hero’s” way of life. Dressed in male attire like the medieval Polovetsian women in real life, such folkloric “women of the field” spend the greater part of their lives in the saddle.

The polenitsy are heroines in the Russian oral epics, or byliny, which are thought to have originated in the ninth and tenth centuries (although they were written down only much later). The byliny are an Old Russian variant of the western genre called gesta (deeds), or popular epic narratives. Their significance in Russian culture lies not so much in the reflection they give of historical events as in what they show about how real events were perceived and understood by the Russian people. The byliny constitute a popular and national narrative response to certain events.

Women warriors, usually portrayed as strong and decisive, are also occasionally mentioned in the Russian chronicles; the way they are represented, however, as is the case with other figures and stories in the chronicle tradition, reveals the influence of the Scandinavian sagas. It is also worth noting that the warrior women one meets in chronicle accounts, in distinction to the female heroes (polenitsy) of the oral epics, usually fight to protect the interests of their men-folk – their fathers and husbands.

The female heroes of the Russian oral epic tradition reveal a great similarity to the legendary Amazons. One of the most well-known female heroes, Nastasya Nikulichna, in her most popular adventure, seizes the brave hero and dragon-slayer, Dobrynia Nikitich, puts him and his horse in her “deep pocket” and carries him around that way for three days until her own steed complains that his load is too heavy and he can’t carry them all any longer. Before pulling the hero Dobrynia out of her “little pocket,” Nastasya Nikulichna responds by sketching out three possible variants of his fate:

Each of the three alternatives Nastasya has in mind for the captured Dobrynia has a parallel in the legendary Amazons’ three basic attitudes to men: openly hostile and murderous; powerful and dominating; or sexually aggressive. In addition, the epic tale, which is well-attested in the oral tradition of the Russian North, portrays Nastasya as a woman of exceptional will and power, traits generally not typical of real-life women in patriarchal Russian society. Unlike most Russian women in the period when the byliny originated, Nastasya has the power to choose her own husband according to her own sexual and emotional needs and inclinations. Like any Amazon, she has the right to control her own body and sexuality: whether she desires sexual intimacy with a man or not, either way it is a matter of her desire of the moment.

In chapter two of this study we shall see that the tendency to so-called masculine (active or aggressive) behavior and the aspiration for sexual and emotional independence that describe the legendary Amazons’ and folkloric polenitsas’ attitudes to sex with men, will become two of the most important, defining characteristics of lesbian women as such women are delineated in the works of Russian authors (mainly male) from the middle ages until the present day. Therefore, it is essential to emphasize that the cultural model of the Amazon or the female warrior (polenitsa) in Russian epic tradition does not specify (or even hint in any way) that the woman who illustrates this model, in folklore or in life, bases her behavior toward men on her sexual preference for her own sex, or that, indeed, being a warrior woman has anything to do with a woman’s sexual orientation or preference per se – if anything, Russian folklore’s female heroes are decidedly heterosexual.

In another Russian oral epic story – about the hero Dunai Ivanovich who kills himself out of love for a polenitsa and is turned into the river Dunai – there occurs a switch in gender roles that is typical for Amazon mythology: it is not the seduced-and-abandoned maiden who commits suicide, but the seducer who does because he is convinced that he has killed the brave polenitsa (who in some variants of the story is pregnant from him with a fantastic infant who is said to shine like a light).

The oral epics about Dunai are also noteworthy because they contain female characters who represent two opposing types of womanhood asserted as cultural models in Old Russian culture. One type is represented by the “princess” Opraksa: she sits in her women’s quarter (tower) “beyond thirty-nine castles,” “weaves beautiful things of silk,” wears golden rings, and is dressed in “just a fine little shirt” and “just fine little stockings,” sporting an unbraided mass of fair hair. Opraksa is the popular ideal of femininity, a secluded maiden sitting in expectation of her predestined bridegroom. In contradistinction to Opraksa, her sister, the polenitsa Nastasya, Dunai’s fiancé, “rides out into the clear field as a [female] field-fighter” and “has great strength in her shoulders”: under her weight her steed “is sunk to its knees in the earth.” This latter formula is applied in Russian oral epic texts both to the male epic heroes and to the female ones.

The polenitsa's of the Russian oral epics typically wear male attire and coats of mail. Aleksandra Ilinichna, the daughter of the most popular and beloved epic hero, Ilya Muromets, has no liking for weaving or spinning, but loves to gallop over broad meadows and clear fields. As we shall soon see, the young Nadezhda Durova, a real-life Russian warrior woman who fought in the Napoleonic wars, also preferred horseback riding to female handiwork, a preference that drove her mother to despair.

Women warriors of Old Russia are not confined to folklore, but apparently existed in real life. Their deeds are chronicled in the written record although it is, of course, sometimes difficult to separate legend from historical fact in medieval chronicles of Russia or any other country. Thus is preserved the memory of a certain Fyokla, the daughter of a military commander by the name of Fili ( a retainer of Prince Yuri Dolgoruky) who was known in the twelfth century as “the Amazon of Rostov” (Kaidash, 48). The Rostov chronicle records that Fyokla was “savage and brave in war, but in peace time exceedingly kind,” and “despite her youth, never turned and fled the enemy.”

In the fourteenth century Rostov chronicles, mention is made of women who took part in the Battle of Kulikovo (1380), one of the most important battles in Russian history. A certain Darya Andreyevna, the daughter of Prince Andrei Fyodorovich of Rostov, dressed in male attire and ran away from home in order to join her beloved (later, her husband), Prince Ivan Aleksandrovich, and take part in the Kulikovo battle (as a foot soldier). Another Rostov princess, Theodora Ivanovna Pushbolskaya-Versha, followed her beloved, Vasily Bychkov, to the Kulikovo battlefield where she was seriously wounded. And so, if one is to believe the chronicle accounts, women like these, in male attire and fully armed, appeared on the historical scene in Russia a half century before Joan of Arc. Unlike the Catholic Church in the West, the Russian Orthodox Church did not consider a woman’s dressing in men’s clothes to be a mortal sin. (In Byzantium, from which so much in medieval Russian culture and morality was drawn, cross-dressing (and freedom in dress, generally) was connected with the profession of circus actresses, the performance of obscene dances and pantomime – one such actress in her youth was Empress Theodora (sixth century), who was subsequently canonized as a saint. All of this was condemned by the church fathers but not considered a mortal sin.)

The Amazons, polenitsa’s and other warrior women in Russian folklore and, possibly, real life laid the foundation of a long-lived and enduring tradition. Russian women had ready access in their culture to variegated examples of non-conformist, trans-gendered female behavior which inspired them over the centuries in some cases to break away from society’s norm of the “feminine,” silent, subservient way of life. At the same time, Russian warrior women have played an important role in the history of Russian women for a number of reasons. First of all, such women constitute a special and distinct minority in the Russian cultural landscape: they are women who fully or in part have rejected traditional female roles and have actively fought against the destiny allotted to them by their patriarchal society. Moreover, they are fully conscious of their rebellion against traditionally constructed femininity. Secondly, modern Russian Amazons have sometimes been aware of the reputation of their ancient foremothers as man-haters and even “deviants,” and yet, they have still consciously adopted the Amazon identity and worn it with pride, regardless of their personal feelings about men and/or their sexual orientation. Thirdly, the Russian Amazons’ distinctive, purportedly “masculine” way of behaving and living has been read by the dominant culture, rightly or wrongly, as a sign, symptom, stigma or natural (in-born) marker of female homosexuality, and this is true even in cases of the most blatantly heterosexual Amazons. There is more than a little irony in the fact that if one adopts the narrowest, and probably most common, definition of a “lesbian” as a woman who is sexually oriented to other women, then it turns out that not a single one discussed so far can be considered a lesbian.

Having established some sort of broad historical and cultural context both in fantasy and fact for understanding what it means for a Russian woman to take up the warrior’s way of life, I shall turn now to the real-life stories of two courageous and remarkable Russian amazons of the not too distant past: Nadezhda Durova and Maria Botchkareva.

In 1836, with the publication of her Cavalry Maiden, Notes of a Russian Officer in the Napoleonic Wars, Nadezhda Durova (1783–1866) made Russian literary history, especially women’s literary history. Durova was not only the first Russian autobiographer whose autobiography was published during his lifetime as Mary Zirin notes in the introduction to her authoritative English translation of Durova’s ground-breaking work. Far more significant is the nature of the story Durova tells: about how she grew up a virtual stranger in her own body and eventually had the courage to realize her true Amazon self by leaving her husband, father and even her infant son, transforming her appearance, dressing as a soldier, and running away to join a cavalry regiment. Durova’s story is one of the first and very small number of narratives about transgendered “identity” and life experience written in Russian in the transgendered woman’s own words. In addition, Durova considered her primary readership to be provincial gentlewomen like herself, whose very restricted lives would have been hers had she not improbably and boldly chosen to transgress just about every gender role norm in her arch-patriarchal society including the cultivation of “femininity,” modest and subservient spousehood, and even motherhood – for which she would have been, perhaps even was, severely censured.

Perhaps anticipating and wishing to escape such censure, Durova, when she resolved to publish her Notes, consciously changed the chronology of her life and did not mention her marriage or motherhood. In the autobiographical introduction to her Notes, which is titled “My Childhood Years,” she presents herself to her readers, as she did to the authorities, as seven years younger than she actually was at the time she enlisted in the army. Apparently, she told the enlistment officer that she was sixteen when in fact she was twenty-three. Throughout her Notes she never once alludes to her (apparently forced) marriage – to Vasily Stepanovich Chernov in October 1801 – or to the birth of her son Ivan in January 1803.

As Carolyn Heilbrun has argued persuasively in her study of women’s autobiographies, Writing a Woman’s Life, the majority of nineteenth- and twentieth-century women autobiographers structure their written lives on a traditional fictional “marriage plot.” Female autobiographers tend to highlight the role of marriage and/or love in their written lives regardless of whether their marriages or love affairs actually did constitute an emotional highpoint in their “real” lives. Durova approaches the telling of her life in an exactly opposite, and notably idiosyncratic way, suppressing her marriage and highlighting the traditionally “unfeminine” aspects of her life. This approach enables her to focus attention on the genuine culminating moment in her real (and utterly unconventional) life – the moment of radical transformation into her true Amazon warrior self who had been stifled by acquired patterns of enforced femininity and compulsory heterosexuality.

It did not take long for rumors that Durova was really a woman to reach Emperor Alexander I, who ordered him/her to appear before him in a private audience. She pleaded with the emperor to allow her to remain a soldier and ultimately, he gave her permission to continue to serve under the male pseudonym she had chosen, “Aleksandrov,” as a junior officer in a regiment stationed on the western frontier of the empire. At the emperor’s request, Durova gave her word of honor never to divulge her true sex, to conduct herself with exemplary courage as a young man of irreproachable morals, un chevalier pur et sans rapproche. (It is very possible that Durova’s desire to keep her word to the emperor played a part in the self-censorship she exercised over her autobiography.)

In 1807 Durova saw action in two battles (at Gutshtadt and Friedland), where she was cited for bravery. During the War of 1812 she fought courageously in many battles and was wounded at Borodino. She retired from the army in 1816 with the rank of Staff-Captain (in the cavalry) and returned to her father’s house in Sarapul. Ten years later, after her father’s death, the office of mayor he had occupied passed to his son Vasily, Nadezhda’s brother. In 1830 or 1831 brother and sister moved to Elabuga where Durova would live till the end of her long life with the exception of a four-year period she spent in St. Petersburg at the height of her literary activity (1836–1840) when several of her works were published.

It happened that in 1829 Vasily Durov had made the acquaintance in the Caucasus of Alexander Pushkin (Russia’s premier poet) who was returning at the time from Armenia. Pushkin described their meeting in the pages of Table Talk, noting that after Durov had apparently lost all his money at cards, Pushkin offered him a seat in his carriage and the two of them traveled together as far as Moscow. In 1835 Vasily Durov wrote Pushkin about his sister’s military journals and suggested Pushkin might be interested in publishing them in his literary magazine, The Contemporary. The manuscript never reached Pushkin and was returned to Elabuga. Then, Nadezhda Durova herself set out for St. Petersburg and handed the manuscript to Pushkin personally in May 1836. Durova’s Cavalry Maiden soon appeared in print, drew critical attention and launched the author’s literary career.

In addition to the non-fictional Calvary Maiden, which earned Durova a permanent place in Russian literature, Durova wrote fiction of the Gothic romance variety, including four novels, among them, Nurmeka. An Event from the Reign of Ivan the Terrible, after the Victory over Kazan (1839). This novel, though written wholly within the conventions of the female Gothic genre, seems to have a certain autobiographical suggestiveness in that it deals with the theme of real and veiled identity. The plot centers on the ‘literally veiled identity of its eponymous “heroine,” the beautiful Tatar girl Nurmeka, whose mother, Kizbek, will allow no one to see Nurmeka’s face, not even her own father. The text suggests…that until her mother lets her in on the secret, Nurmeka/Selim is unaware that “she” is male. … This particular transvestite masquerade allows its wearer to avoid the heterosexual imperative, but only temporarily’ (quoted from an unpublished paper by Professor Susan Larsen, pp. 8, 10).

In distinction to the “heroine” created by her literary imagination, Durova/Alexandrov’s male identity appears not to have been a masquerade. Once s/he left the military, s/he not only maintained her masculine dress and manners, she wrote and spoke of herself as a man, using the masculine gender endings of adjectives and past tense verbs required of male speakers and subjects in Russian. In socializing she also felt comfortable with her chosen masculine identity. Describing her meeting with Pushkin, she comments that when the great poet kissed her hand, she became embarrassed, blushed and said: “’Oh my goodness! I’ve long since become unaccustomed to such things!” And she notes with self-irony that Pushkin probably “had a good laugh” about the episode after she had gone. Durova went so far as to demand that her own son address her as Mr. Alexandrov (Durova, 17).

When her brother died, Durova continued to live a solitary life in Elabuga, her only known house-mates being the numerous abandoned cats and dogs she rescued. She was known in the town as the local eccentric. Almost nothing is known about her personal life except that she apparently took little interest in her son, who was brought up and cared for by her husband and his family, even when the boy expressed a desire to renew relations with his mother. At the beginning of the 1860s, with the advent of a women’s liberation movement in Russia, Durova was visited by young people who admired her for her unorthodox lifestyle. She accepted her sudden fame as an icon of female liberation with her usual self-effacing modesty and was known for her generosity to anyone in need of money or shelter. She died in 1866 at the age of eighty-three and was buried in Elabuga with full military honors.

Durova’s short autobiography, “My Childhood Years,” is a remarkable, one-of-a-kind work in Russian letters, for which we can only be grateful to chance as well as to the fact that such a radical transformation story as Durova tells actually took place in reality. In this brief, often moving account of childhood and adolescence, we hear the story of a modern-day Russian Amazon, of how she struggled against a significantly better-armed “opponent” to realize what she recognized from her earliest years to be her inevitable destiny – to become in reality the warrior she felt herself to be, despite her feminine exterior, in spirit. Durova’s story is specifically Russian, but at the same time it is universal in what it tells us of a warrior woman’s struggle for self-affirmation and self-realization in patriarchal society, which does not encourage its women to be warriors, but takes pride in those who buck social convention and do.

Although Durova credited her “warrior proclivities” to her father (Durova, 55), the model for her future rebellion seems most likely to have been her mother, Nadezhda Ivanovna (1765–1807), a morbidly depressed woman in later life who had as a young woman endured the curse of her father when she rebelled against his patriarchal authority and married the man she loved without her father’s consent. Durova writes: “My mother’s actions…were so contrary to the patriarchal customs of Little Russia [Ukraine—DB] that my grandfather, in the first flush of anger, put a curse on his daughter” (Durova, 50). Durova’s mother apparently did not take to the role of mother, either: when pregnant she dreamed passionately of having a son, and, as Durova suspected, she was massively disappointed at the sight of “the poor creature whose appearance had destroyed all her dreams and crushed all her hopes” (Durova, 51).

Her mother’s lack of love for her daughter sometimes expressed itself in truly cruel behavior to the infant: once, in a fit of rage, the mother threw her baby out the window of a carriage. It was after this incident that Nadezhda’s father took the upbringing of the girl on himself and evidently began to encourage her interest in things military and the soldier’s life: one of the hussars in her father’s regiment, Astakhov, took over the duties of a nanny for Nadezhda.

Many stories of rebellious daughters begin with the young girl’s perception of a bitter truth – that her mother had wanted a boy rather than her. In aspiring to become a soldier and perhaps unconsciously wishing she were the boy her mother desired, Nadezhda Durova understandably was trying to realize her mother’s unarticulated dreams, all the more so in that her mother, she later wrote, “was oppressed by the bitterness of her situation, and … would paint the lot of women in horrible colors” (Durova, 71). Mrs. Durova battled constantly to make her willful daughter submit to the inevitability of a woman’s fate. It is worth noting that many years later, Durova would abandon her own child, in a sense realizing in fact the model of rejecting maternity that her own mother had acted out towards her. Durova recalled that all through her childhood her mother seemed to want to break her will while she was just as stubbornly bent on affirming it. Self-awareness and the instinct for self-preservation taught Durova the self-reliance necessary for slipping away from her mother’s supervision and “ever-vigilant eye.” The outcome of this almost archetypal struggle between mother and daughter was clearly summarized by the adult Durova: “With each passing day I became bolder and more enterprising and, other than my mother’s wrath, nothing in the world frightened me” (Italics mine—DB. Durova, 58).

Durova’s autobiographical sketch makes clear that from earliest childhood she suffered various painful variants of “not fitting in.” She saw physical signs of “un-femininity” in herself and her consequent alienation from her own female body was exacerbated by her mother, who unconsciously contributed to her daughter’s negative female self-image, as one concludes from the following comments which reveal how Durova viewed her infant and child self with her mother’s eyes: “But alas! It’s not a son…it’s a daughter, and an epic hero (bogatyr) of a daughter at that!”; “I was unusually large, had thick black hair and screamed loudly”; “But my mirror and my mother would tell me every day that I was positively ugly”; “I was very strong and hearty, but impossibly loud”; “Every day I drove her mad with my strange pranks and knightly spirit”; “My military proclivities intensified and with each passing day, so did my mother’s lack of love for me” (Durova, 51–62).

In dealing with the past, Durova wanted to be impartial to her mother, preferring not to condemn her, but rather to express compassion for her sufferings. Yet, occasionally she allows poorly concealed jealousy for her younger sister, Cleopatra [sic!], to rise to the surface of her “objective” narrative: “For her comfort Mama had another daughter, one as beautiful as a cherub, who was, as they say, the apple of her eye” (Durova, 54). As she matured and became a young lady, Nadezhda showed neither an inclination nor any ability for female handiwork, especially lace-making, which she was forced to learn how to do.

When she had turned ten, Nadezhda had already resolved to become “an Amazon”: “to learn to ride horseback, shoot a rifle, and having changed into male attire, leave my father’s house” (Durova, 56). (Without in any way doubting the chronology and firmness of Durova’s desire to make herself into a warrior, one should keep in mind that she is writing about her past with hindsight and clearly wants to present the trajectory of her idiosyncratic and even shocking vocation as unswerving and as rooted in her earliest conscious moments as possible without stretching her readers’ credulity. Her actual development into a warrior may not have been so single-minded or free of conflict and confusion as she represents it in her autobiography. Nor can one say to what degree she constructs her Amazon life on the cultural and literary models available to her in Russian folklore and Greek mythology. All we know is what Durova became, the details she provides of the becoming are believable and have psychological credibility, but, ultimately, they are anyone’s guess – even, the autobiographer’s own.)

Two years after Durova had resolved to become an Amazon, her father gave her a Circassian colt named Alcides and all her “plans, intentions and desires focused on that horse.” She daydreamed about dangerous adventures and despite her mother’s strict discipline and even threats of dire punishment, she claims never to have swerved from realizing the plan she had made: “I had made up my mind though it cost me my life to separate myself from the sex that, as I thought, lay under the curse of God.” She writes that “two feelings of a most contradictory nature” excited her and influenced her decisiveness: “an aversion to my sex” and love for her father who would often say that if he had a son “instead of Nadezhda,” that son would support him in his old age. (Durova, 62)

At a certain stage of growing up Durova underwent a crisis; it seemed for a while that she was ready to betray her intentions to become a soldier and that even “the role of a woman” did not appear “so terrible” to her. In her reminiscences she attributes this momentary change of heart to her new environment and circumstances when she was sent to Little Russia to live with her relatives there. Her grandmother Aleksandrovicheva seemed to have played the role of guardian of proper gender-role behavior at the decisive moment in her maturation – for her grandmother and all her Ukrainian relatives were, Durova writes, “unremittingly hostile to military tendencies in a young woman,” and her “relatives expressed genuine horror…at the mere thought of what were in their opinion illicit and unnatural behaviors in women and especially marriageable girls!..” (Durova, 63). While at her grandmother’s she made friends for the first time with a girl her own age (“we were inseparable”) and she also found herself attracted to a young man by the name of Kiriyakov (whom she also calls Kiriyak), who wanted to marry her. His mother, however, forbade the marriage due to Durova’s dowerless condition. This unhappy end to her first love, according to Durova, decided her Amazon destiny once and for all: “It was my first attraction and I think if I had been allowed to marry him, I would have said goodbye forever to my military plans” (Durova, 64–66).

In general, one gets the feeling that Durova’s story of her childhood and adolescence is deliberately set up to lead to its culmination in radical change and transformation. She fixes the moment of transformation on her name day, 17 September, when she says she was sixteen (in reality, at this time she was twenty-three and had returned to her father’s house, after abandoning her husband and infant son). She writes that just before carrying out her plan (or the plan determined for her by fate), she spent the greater part of her time with her father. Several years earlier, the father whom she so adored had betrayed his wife and thus become the cause of the unhappy woman’s emotional breakdown. After discovering her husband’s infidelity, Durova’s mother began to complain even more bitterly about the tragic lot of womankind: “My mother, under the burden of her sorrow, now painted the lot of women in even more horrible colors. Martial ardor flared up with incredible force in my heart, … I truly began to seek for ways to realize my previous intention of becoming a soldier…” (Durova, 71). Despite the fact that Durova may have found a model for her future transgendered self in her father’s soldierly image and despite her openly writing of her desire “to be a son for my father,” – one still has to acknowledge that what ultimately pushed her to transform her life and identity was a feeling of outrage for the marital betrayal her mother had suffered as well as the deeply felt need to support her own “martial ardor,” which alone would give her the chance to save herself by “separating herself from the sex whose lot and eternal dependency had begun to terrify” her (Durova, 71).

A psychological explanation of Durova’s motivation for becoming a soldier might seem to contradict the traditional opinion that she acted out of patriotism in joining the army. On the other hand, the psychology of her behavior is rooted in her real-life circumstances at the time she took the final step in what would prove to be an utter rejection of female self-identification. Of course, she is silent about those circumstances in her memoirs. Around the time she rejected a woman’s lot for herself, she had already distanced herself sufficiently from her mother to be able to observe the latter’s life without participating in it directly. The position of outside observer must have facilitated the first spark of compassion in her daughter’s heart. At the same time, due to a certain degree of socialization to the gender role expected of a young lady that Durova did undergo in adolescence (something that delighted her mother: “It gave her pleasure to see that I had acquired that modest and devoted behavior so appropriate to a young woman”), – due to her acquisition of socially-approved, young-lady manners and demeanor, Durova must have also gained a personal idea of “the bitter lot” of women about which her mother constantly complained while doing absolutely nothing to help her daughter avoid that lot.

Unfortunately, we simply do not know the circumstances that made Durova decide to leave her husband and son. Perhaps she found herself in her marriage in the same humiliating position as her mother had been in hers and she left her husband, a man she did not love and had been forced to marry, probably for financial reasons, because he had been unfaithful to her. In any case, the very fact that she fled her husband’s house and abandoned her child speaks eloquently to Durova’s extreme dissatisfaction with the roles of wife and mother, while the apparently celibate life she lived for the ten years she served in the army suggests that an active sexual (or even personal) life was hardly a primary consideration for her. She clearly thought the sacrifice of a sexual life was worth making as the necessary condition for serving in the imperial army as a man. Actually, we know nothing in fact about Durova’s sexuality. Since she preferred not to mention her marriage in her autobiography, one can assume that she would have maintained silence about her intimate life regardless of the nature of her close relationships or whether or not she had any such. What does ring loud and clear in Durova’s autobiography, however, is the exalted, detailed and even grandiose narration of its most important event – a true ritual of transformation into a new self.

From the very start Durova’s description of the feelings she experienced during her transformation is conveyed with a certain solemnity and consciousness of the importance of the moment. She is being born into a new life and acquiring another self: “The seventeenth was my name-day as well as the day, whether by fate, the confluence of circumstances, or an unconquerable proclivity, it was fated for me to leave my father’s house and begin a completely new sort of life” (Durova, 72). Durova takes the autobiographical heroine (that is, her self) through a number of rituals that smack of an initiation. Everything takes place against a symbolic backdrop: “At that time day had begun to dawn, it would soon spread out its scarlet blaze and its splendid light, flowing into my room, illumined its objects.” The narrative is saturated with the archetypal symbolism of transformation. Her room here represents her herself: the light suffuses her and illumines “all objects” and circumstances; moreover, her “father’s saber, hanging on the wall…appeared to be aflame.” When Nadezhda takes the saber in her hands, sheathes it and girds her loins with it saying: “‘I shall wear you with honor’” – she seems to be symbolically putting on a new, male self. Later, as soon as everyone in the house had awakened, the time comes to accept her name-day gifts from her parents and her little brother; none of her family naturally suspects that their gifts are also farewell presents. Nadezhda spends the whole day with her girlfriends like a traditional betrothed before her wedding.

Then, Durova describes saying good-night to her parents who again do not realize that this nightly ritual has a special double meaning for their daughter: she was saying good-night to them and good-bye to her whole past life. She believed she would probably never see her parents again. Blessing her wayward daughter for the night, her mother was touched by the tenderness and obedience Nadezhda uniquely manifested on this occasion. As a result, the good night was much more emotional than usual, and Durova chose to perceive it as a parental blessing to join the army. Alone in her room after the house had grown still, she set about transforming her appearance: she removed her feminine clothes, put on “a Cossack uniform” and cut her hair. She rode away from her home astride her beloved horse Alcides, having left her female clothes on the bank of the river. While hoping her father would not think she had drowned, she reasoned that the pile of clothes would give him a way of answering any “embarrassing questions” from acquaintances and insure he would not suffer any shame for his daughter’s mad deed. Durova set out for the village where she knew a Cossack regiment was stationed in order to travel with the Cossacks to the regular army.

Several remarks at the beginning of Durova’s Notes make it clear that it was not easy for her to get used to her new identity. It is often difficult to understand whether or not Durova is being purposefully or simply unconsciously ironic in her autobiographical narrative when she describes her first experiences as a young enlistee. There is a certain ambiguity in how she herself and those around her perceive her once she has cross-dressed in male attire. For example, she writes: “I was very aware that the Cossack uniform poorly concealed my striking difference from the native-born Cossacks” (Durova, 85). A comment like that suggests that in her own eyes she was still a young woman playing the role of a man in a kind of comedy of cross-dressing, and not playing it very well. She notes that the other Cossacks had “a definite look about them” that she did not have. She doesn’t give any details about what made their appearance so different from hers, although it is not hard to guess – perhaps their beards, rough sunburned skin, “masculine” aspects in general, or their clothes and behavior. Later, when she had left the Cossack regiment and joined a cavalry squadron in which many of the new recruits came from her social class, she remarks on how well she fit in with the boys who struck her as more similar to good-looking young ladies than virile soldiers (Does she catch the irony in such a remark, or not? .One can’t be sure.). Durova thought that the white and gold uniforms and young age of many officers helped to diminish the difference in appearance between her and the men. Therefore, it is possible to suppose that in Durova’s opinion, she stood out in the Cossack regiment more because of her manners than her “poorly disguised” female gender. In actual fact, during her military career, more than one of her comrades suspected that “Aleksandrov” was a woman, but apparently no one acted on his suspicions which remained in the realm of unconfirmed rumor.

One of the most vexing problems Durova confronted at the beginning of her military service was getting used to wearing standard military dress (which could be considered a metonym for her new role, identity and lifestyle). It was especially hard for her to wear the “tyrannical official boots.” But she overcame these difficulties and accepted the suffering the military boots gave her with stoical endurance: “One has to endure what can’t be changed” (Durova, 103). Such a philosophical approach may provide a key to understanding other and more profound aspects of Durova’s inner life, as well. Perhaps, she had endured her woman’s lot so long as she thought it impossible to change or go against her sex; her biological femaleness was for her that pair of “tyrannical” boots that she was obliged to wear. Although she accustomed herself to the heavy “boots” of femininity, so to speak, she nevertheless realized even at the age of ten that change was possible and her hopes for the inevitable change lay festering deep within the recesses of her soul.

Durova experienced some anxious moments during the formalities of enlisting in the active forces; they were connected, however, not with the issue of her gender, but with the need to prove her class standing as a member of the gentry-nobility. In addition, because of her youthful appearance she was required to produce a letter from her father giving her permission to join the army. In relating how she coped with these official hindrances on the path to realizing her life’s dream of becoming a soldier, Durova sometimes adopts an openly ironic tone, or risks sounding disingenuous. She reports that the Cossack colonel advised her “to be open” with the commander of the regular regiment she decided to join: Since she had no documents attesting to her noble origins she could not become a cadet. She followed this advice, which results in one of the most ironic and even farcical moments in her Notes when one of the officers, in reply to the cavalry captain’s doubts about accepting an enlistee without the proper attestation of nobility, allegedly said: “It’s written all over his face that he’s not lying, at that age they don’t know how to dissemble” (Durova, 98. Italics mine—DB).

But the issue of parental permission was not resolved so easily and lightheartedly. After Durova had already tasted fire and fought courageously, her regimental commander, General Kakhovsky, brought the issue up: “Kakhovsky asked me if my parents had given me permission to serve in the military and if I hadn’t enlisted against their will. I told him the truth straightaway that my father and mother would never have allowed me to enter military service” (Durova, 149). She adds immediately that she had begun to have doubts whether Kakhovsky did not “know more about [her] than he let on,” – since he had not expressed surprise “at the strangeness of [her] parents’ attitudes.” Most parents of young gentlemen would have encouraged their children to become soldiers. Durova appears to have felt that Kakhovsky suspected she was a woman.

Despite passing successfully as a man among the people around her, Durova herself continued to feel like a woman playing the role of a man, albeit ever more convincingly, until she was able to recognize herself as male in her own eyes. Preparing for a visit with her father after a separation of almost four years, she thought about the changes he would see in her, yet in pondering this, she rather surprisingly (at least for a contemporary reader) does not even consider the most obvious change: the effect of having lived as a man, talked as a man and having appeared to be a man for such a long time. Rather, she notes simply that her father will no doubt notice that she has grown up, filled out, matured. Narrative moments like these, though hardly numerous, suggest either that Durova was not always able to create convincing fictions to conceal the gaps in her autobiographical, as opposed to real, life, or that her performance of masculinity was not so seamless as she wants her readers to believe.

It is worth noting in this respect Durova’s frequent feeling that the women she happened to meet during her time in the army were far more suspicious of her being a man than the men, and for that reason she tried to avoid the company of women. At the same time s/he attracted the attention of gentlewomen in the provinces of the western borderlands when her regiment was stationed there. The parents of one young lady even looked upon “Aleksandr Durov” as a potential suitor for their daughter’s hand. Nevertheless, one cannot say with complete assurance that Durova shunned the society of women only because she feared (or wanted to believe she feared) exposure, or, for that matter, because female society was too attractive to her, and not necessarily in a narrow sexual sense. One of the chief joys of her young life had been the friendship of girls her own age, and in essence, such friendships constituted her sole source of comfort and reconciled her to the life of a young gentlewoman. Having chosen the life of a soldier (and it is important to emphasize Durova’s insistence that her fate was “chosen of [her] own free will”), she nevertheless at first suffered feelings of homesickness, longed for “the attire of [her] sex,” but she swore “never to allow such memories to weaken [her] spirit” and shake her resolve to become a true soldier.

There is no doubt that Durova was a woman who felt from earliest childhood a virtually unbridgeable gap between her sex and her calling in life. As an adult she made the courageous, and for her times extremely unconventional decision to sacrifice almost everything expected of and for a noble woman in her society. The gender role demanded of her by culture and tradition must have created an extraordinary conflict with her desire to realize the Amazon aspirations that took root in her at the age of ten. The pressure of conflict between cultural (societal) expectations and personal inclinations built to the inevitable breaking point and Durova’s “fate” was decided.

The contemporary Russian sociologist Igor Kon considers Durova a lesbian before the name, so to speak. He expresses the opinion that if we knew more about her biography, we would probably discover in it “the tragedy [sic!] of transsexualism” (Kon, 228). While I would have to disagree with the notion that there was anything “tragic” in the life of Durova (or any woman) who could say that she had achieved her most cherished life’s dream (and it is interesting that the contemporary Russian poet Elena Schwarts – in her poem about Durova quoted as an epigraph to this section – clearly also senses something tragic in Durova’s radical change), I agree that judging by Durova’s memoirs, she experienced feelings of gender discomfort and being born in the wrong body of the sort which have been experienced by other transgendered women, or “transgendered warriors,” as Leslie Feinberg calls them in her monograph on the history of such individuals from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman. Indeed, Durova could well have been included in Feinberg’s study.

There is nothing surprising as well in the reputation Durova has acquired in her native land where most Russians who have heard of her have considered her to be a kind of Russian Joan of Arc, first and foremost, a patriotic woman and warrior maiden. Representing Durova as a Joan of Arc wannabe is, at least, a useful way to explain historically how she was able to achieve what she achieved. And Durova herself laid the groundwork for the enduring image of patriotic Russian womanhood that posterity has devolved on her. Of course, even today the majority of Russians who have heard of Durova probably do not know that she left her husband and infant son in order to become the Russian Joan of Arc, facts that seriously undermine the Joan of Arc myth in which the heroine’s maidenhood is a vital element. One has to credit Durova’s understanding of her readership: she wisely preferred to leave out of her memoirs what would have testified to her heterosexual, hence “normal” femininity but would have simultaneously contradicted the far better cover story of “a Russian maid of Orleans,” that she writes out of her life.

At this juncture, it is worth making a small digression in order to mention the well-known film of E. Riazanov (screenplay in verse by A. Gladkov), “Ballad of a Hussar,” based on Durova’s life. Released in 1962 for the hundred fiftieth anniversary of the War against Napoleon, the film is a prime example of high pop at the peak of the Soviet “Hollywood Style.”

The heroine of the film is called Shurochka Azarova despite her openly proclaimed real life prototype’s being Nadezhda Durova. Shurochka is a very feminine seventeen-year-old girl. Although she is in love she hates coquetry and courtship games; patriotism motivates her to go to war where she demonstrates irreproachable courage and bravery except for one thing – she is afraid of mice. This endearing feminine weakness is what reveals her in the end to be a woman who is merely disguised as a man. Leaving aside the traditional plot twists that are part and parcel of cross-dressing stories, – jealousy, women falling in love with the cross-dressed girl, and so forth – the film shows how the young virginal heroine, an orphan and a daredevil, is rewarded for her brave deeds by winning the hand of her comrade in arms, a fine fellow who saves her life. And so, the idiosyncratic, unconventional and elusively complex warrior woman Nadezhda Durova finds her enduring place in Soviet-Russian popular culture disguised as a conventional, spunky ingénue out of Shakespearean comedy or French farce.

To whatever category or model or personality type one might decide to relegate the “real” Nadezhda Durova (and such an attempt is probably futile), what she wrote about herself convinces one that the main motivating factor behind her transgendering herself lay in her desire for freedom, freedom especially from the shackles forced by her patriarchal society on her as on all women:

Like the majority of non-conformists, Durova both consciously and unconsciously experienced various feelings of alienation. Judging from her autobiography and her Notes, there were physical, social and spiritual reasons for her alienated feelings. From her earliest years she grew accustomed to thinking that her having been born female was a mistake of nature and that she was a poor and even ugly specimen of her sex. She was “an epic hero of a daughter,” and although the Russian national epos celebrates a number of female heroes as we have seen at the beginning of this chapter, it is safe to say that at the turn of the nineteenth century few if any daughters of the provincial gentry aspired to the female-hero model. With the exception of the few years in adolescence Durova spent away from her far-from-ideal birth family, during which time she was not pressured and disciplined into leading a young lady’s life but rather enjoyed the loving attention of women and young men, – with the exception of those years, throughout her whole life Durova apparently felt alienated from the prescribed rules of feminine behavior upheld and enforced by her time, class and social milieu. Indeed, it is hard to imagine a more limited lifestyle than the typical one of a poor provincial young Russian gentlewoman of Durova’s time. Although such women possessed the right to own and dispense of their own property, they nevertheless found themselves in complete dependency on their husbands and fathers (in the event they did not marry or left their husband). They could not live or travel alone without the men who were in effect their guardians. The only way for them to achieve a certain degree of independence without incurring social censure was to enter a monastery and become an abbess or to be widowed and not remarry.

Constantly feeling at odds with the un-free condition her society condemned its female citizens to, Durova found herself congenitally unable to reconcile herself to the gender role prescribed for her – and this inability to accept her life as it was seems to have been the main reason why she decided to change at least the image of who she was and adopt a male image, if not “identity.” There is, of course, no small irony in the fact that the male image and role she chose in order to liberate herself turned out to be a prison of its own in other ways as perhaps Elena Schwarts intuitively grasps in her lyrical evocation of how Durova became “alien to herself.” Leading the life of a soldier who could not forget, even for a moment, that she really was not one of the boys, must have enhanced her already keenly felt sense of aloneness and separateness, not to mention the anxiety it necessarily brought, at least at first, to be constantly on guard, ever vigilant not to allow the smallest slip (even in grammar!) in her demeanor and habits that would give away her underlying female self. To live a lie for ten years as Durova did, even if the lie appears to be true in some sense to the liar (as it did to Durova), demands an uncommon amount of willpower, energy and self-control. Whether such a person wants to or not, he becomes, of necessity, lonely, restrained and secretive, all qualities that are reflected in the way Durova narrates her life: her voice is concertedly dispassionate and un-emotional.

There can be no doubt, however, that Durova ultimately made her chosen male identity her own, that she completely grew into the new persona she designed for herself and felt utterly comfortable and free in it. Whether out of long-standing habit or because of the in-born nature of her male identity, Durova maintained her male attire, speech and way of life after she retired from the army and ultimately lived the greater part of her long life as a man. At the same time, she preferred the life of “a man” on the margins, shunning the company of people in favor of her beloved animals. In my opinion, it is fair to say that from an early age Durova had an image of her self not so much as a woman or a man but as a soldier. Being a soldier was not only a vocation for her and a realization of a professional dream, but some sort of personal grail, achieving which allowed her to transform her whole life.

Thousands of women in history have cross-dressed and lived as men, at certain times and in certain countries risking severe, even capital punishment if their true sex was discovered. By comparison with many transgendered or passing women, Durova led almost a charmed life. She suffered no persecution from family, society or the law for the transgressive life she led. The greatest risk she ran was the humiliation of exposure while she served in the army, and after she retired, the inevitable possibility (and perhaps, reality) of being thought of as a freak and a curiosity.

Yet Durova, and women like her, cannot help but stand out in the context of traditional Russian society with its strong sanctions against open social non-conformity. Durova rebelled against one of the most basic of strict binary categories that humans insist on enforcing on themselves. It is still true, in the twenty-first century, as it was two hundred years ago in Durova’s youth, that one’s sex determines a lot of one’s life. Durova’s bold decision to make her gender not a given, but a choice, and to live accordingly, challenges very basic assumptions that her society, and most others, made and continue to make about human identity and personhood. As Schwarts notes, “Most people shun such sudden shifts,” which is why, the poet surmises, Durova was a social outcast, a pariah by choice or necessity. Yet pariah-hood obviously has its rewards that inevitably radiate from within.

The Russian Amazon I shall turn to now, Maria Leontievna Botchkareva (1889–1920), differed greatly from Nadezhda Durova in terms of her class, education, motivation for becoming a soldier, status among her male comrades in the army, and the voice in which she narrates her autobiographical account of what can only be described as an amazing life. The ebullient, chatty and discursive style of her oral autobiography, Yashka, may be partially explained by the fact that Botchkareva, who was only semi-literate, dictated her life story to an American journalist, Isaac Don Levine, who then translated it into English and published it in 1919. Botchkareva recounted her story to Levine while she was in the United States in the late spring of the previous year. She had traveled to America with the help of the British Consulate in order to petition President Wilson to intervene in the Russian civil war on the side of the anti-Bolshevik Whites. Botchkareva’s decision to tell the story of her life may have been politically motivated – she was at that time passionately anti-Bolshevik and had put her military experience and Russian patriotism at the service of the Provisional Government before the October revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power. As part of her service to the Provisional Government she had won the support of President Rodzianko in May 1917 to form and lead an all-woman battalion (the so-called Battalion of Death), the purpose of which was to buoy the very flagging spirits of Russian (male) soldiers at that point in World War I and try to stop the mass desertions of Russian troops from the front.

Botchkareva’s father (Leontii Frolkov) was a former serf in Novgorod province. Liberated at the age of fifteen, he later fought in the Russo-Turkish War, received several medals for bravery, learned to read and write, and earned promotion to sergeant. Her mother, Olga Nazariova, was the daughter of a destitute peasant, and Maria was the third daughter born to her and Leontii. Maria describes her childhood as fraught with violence, poverty and insecurity. Her father, unable to find work, turned to drink and abused his wife. He left his family for five years when he went to St. Petersburg in search of work. When he returned, he fathered another daughter, and the destitute family moved to Siberia where they received land in Kuskovo, about a hundred miles from Tomsk, in the middle of the taiga.

Maria says she went to work at age eight-and-a-half (not uncommon for girls of her class at that time in Russia) and also suffered abuse from her father when he was drunk. At fifteen, she married a peasant, Afanasy Botchkarev, who turned out to be an abusive alcoholic as well. Using her mother’s passport, Maria tried to run away to the home of a married sister, but eventually, her husband caught up with her at her sister’s. When Maria threatened to drown herself, he promised to go sober if she would come home. Of course, he took to drink again and became so abusive Maria tried to kill him. Stopped from committing this desperate act by her father, Maria left home and eventually made her way to Irkutsk. There she entered into a common-law marriage with Yakov Buk, a small-time confidence man masquerading as a political fugitive, and followed him into exile in Kolymsk. Their relations became increasingly strained and when they turned violent and Yakov tried to kill her, she returned to Tomsk. There, at the start of World War I and against the objections of her parents, especially her beloved mother, Maria enlisted in the Tomsk Reserve Battalion, having obtained special permission of Emperor Nicolas II to do so. Unlike Durova, Botchkareva did not hide her sex from the army or her fellow soldiers. She did adopt male dress and a male pseudonym (strangely taking the name of her murderous ex-lover) and insisted on being treated like any other enlisted man, refusing the private officers’ quarters she was initially offered by her commanding officer in deference to her sex. At first, Botchkareva reports, her fellow soldiers subjected her to considerable hazing and harassment, but when they realized she was serious about being a fighting soldier and had only comradely feelings toward them, by her own account, they accepted her as “one of the boys,” stopped harassing, and became protective of her.

From 1915 to 1917, Botchkareva served on the southwestern front of the Russian empire, in basically the same region where Durova had served just over a century before. She saw longer and more active combat than Durova had, was decorated three times for bravery under fire and eventually received all degrees of the Order of St. George, the highest military honor in Russia. (The editors of the anthology Lines of Fire who include two excerpts from Botchkareva’s memoirs in their book are incorrect in repeating the misinformation – perhaps culled from Botchkareva herself – that Botchkareva was denied the highest degrees of the Order of St. George because she was a woman.) Botchkareva was wounded at one point by a piece of shrapnel that lodged in her spine and nearly paralyzed her, but she recovered and returned to combat. For rescuing wounded comrades in No Man’s Land she was promoted to corporal.

Botchkareva greeted the end of tsarism enthusiastically, but she became appalled by the military confusion and attitude of defeatism among the Russian troops that followed in its wake. Her outraged patriotism and apparently genuine love for her motherland – for her Russia was always a mother in need of protection and help from her daughters – led her to come up with the idea of forming the all-women’s Battalion of Death mentioned earlier. Proselytizing for her battalion, she proclaimed at a recruitment meeting in Petrograd: “‘Our mother is perishing… I want to help save her. I want women whose hearts are pure crystal.’” (Quoted in Lines of Fire, p. 157). Words like these with their direct appeal to female solidarity, patriotism and most important, pride in being female accurately reflect Botchkareva’s attitude to her gender and provide insight into what must have motivated her to transgress the gender-role norms of her society and become a combat soldier.

Botchkareva emerges quite un-self-consciously in her oral autobiography as a totally unschooled, spontaneous ‘feminist of the people,’ whose primary aim was to prove that women are every bit the equal of men even at the sort of endeavors such as the combat military that patriarchal societies deem inappropriate to their sex. When Botchkareva first attempted to enlist in 1914, the enlistment officer welcomed her but assumed she wanted to be an army nurse or serve in a supporting role in the rear. Because she insisted that she wanted to be a fighting soldier, she had to obtain special permission from the highest authority in Russia, the tsar himself, in order to enlist. By her own account, Botchkareva wanted to prove through her example that women could fight as bravely and as well as men. Later on in her military career, one suspects that this Russian Amazon may have wanted to prove the superior fighting ability and certainly, the more stalwart fighting spirit and patriotism of Russian women.

Botchkareva makes no bones about her chief intention in forming the women’s Battalion of Death: She was convinced, naively and dangerously, that the sight of thousands of fighting women would transform the defeatist psychology of the exhausted male soldiers and shame them into going on the offensive. With this intention firmly in mind she created and trained her women’s battalion (in May 1917) to be tougher than tough, more macho than macho, almost an unconscious parody of the disciplined, brutally hard Prussian troops, sworn to fight to the death, unflinchingly. Although two thousand women enlisted in Botchkareva’s battalion, her iron discipline caused many enlistees to drop out and in the end, she had at her command less than three hundred women. Her soldiers addressed her as “Mister Commander” “since [as she explained] all military terms are masculine and it is much too useless a work to go through the list feminizing the nomenclature of war.” (Quoted in Lines of Fire, p. 158)

The Women’s Death Battalion fought competently and bravely on the western front, suffering casualties and taking German prisoners. The women in the battalion carried cyanide of potassium in case of capture. In a July attack, Botchkareva’s troops took two thousand prisoners while suffering only seventy casualties; yet their heroism and military success enraged many fellow soldiers who accused Botchkareva of provoking counter-attacks from the Germans that resulted in even more Russian deaths. Finally, the battalion was disbanded in September 1917 for essentially two reasons: Botchkareva failed to transform the psychology of the male soldiers as she had hoped to do – politically naïve, she apparently did not realize that the mass desertions had a political character and were in large part the result of propaganda carried out by the Bolsheviks, whose insistence on ending the war was at the heart of their political success. Secondly, the Bolshevik agitators increasingly threatened the lives of female soldiers inspired by Botchkareva. Botchkareva herself did not give up so easily. A supporter of the anti-Bolshevik General Kornilov, she and members of her battalion regrouped in Petrograd after the Provisional Government was overthrown and participated in the defense of the Winter Palace during the Bolshevik coup. Twenty of Botchkareva’s women soldiers were lynched and others were severely beaten by male soldiers.

Botchkareva’s Women’s Battalion of Death was not the only example of Russian women assuming a combat role in World War I. The Women’s Perm Battalion also saw action at the front lines, and other women’s battalions, with up to a thousand soldiers, guarded Moscow and Petrograd. Members of the First Petrograd Women’s Battalion also took part in the defense of the Winter Palace on the night of the Bolshevik coup. At the end of his article on “The Impact of World War I on Russian Women’s Lives,” Alfred G. Meyer discusses the large number of female combat soldiers in Russia as a specifically Russian phenomenon in the context of the other major combatants in the Great War:

Meyer goes on to note that “Russian feminists differed sharply in their attitudes toward these warrior women. The Women’s Herald, a radical feminist journal…expressed approval; but Women’s Affairs, a “ladies journal,” suggested that the fighting forces were not a suitable place for a woman.” (Meyer, 220) It is clear that Russian “Amazons” were chided, if not condemned by many Russians for abandoning their “femininity,” for challenging the traditional gender role of women in Russian society as compassionate, helping and healing. Most Russians believed that women who wanted to participate in the war should become nurses. “Indeed, at the beginning of the war so many women sought to serve as nurses with the troops that large numbers had to be turned down” (Meyer, 220).

The people Botchkareva really hoped to influence through her personal example and her organizing of the Battalion of Death were the deserters, the pacifist and/or bolshevized rank and file of the Russian army, and it has to be said that she failed in this effort (as she herself admitted freely, if regretfully). Unintentionally, she succeeded only in insuring the future universal Soviet disparagement of her and the Women’s Death Battalion.

Botchkareva returned to Soviet Russia in August 1918 together with an Allied invasion force. She wanted to assist the White armies that were organizing in the North to fight the Bolsheviks, speaking out at meetings despite being greeted with incomprehension and derision. In December 1918 Botchkareva paid an official visit to Marushevsky, the commander of the Army of the North, offering her services to help train and organize the troops. In response Marushevsky issued the following order, which said, among other things:

In October of 1919 Botchkareva set out for Siberia with the government of the North’s naval expedition. At the suggestion of A.V. Kolchak, who apparently did not share Marushevsky’s notion of shame, she formed a voluntary guard detachment of the Red Cross. After the defeat of Kolchak’s army, Botchkareva returned to Tomsk. The last months of Botchkareva’s life are described in a recent article by a Russian historian, S.V. Drokov:

What Botchkareva did accomplish in the military example she set was to place the question of fighting women on the agenda for Soviet Russian society. Despite the “heavy reproach and shameful stigma” their Amazon ardor risked bringing upon “the whole population,” large numbers of Russian women fighters volunteered in the Civil War and by 1920, twenty thousand women were serving in the Red Army.

The lives, Amazon aspirations and careers of Durova and Botchkareva – and I have chosen to compare them because they, almost alone among the thousands of women warriors in Russian history, managed to leave written and recorded testimony of their lives – yield a number of instructive comparisons which can tell us a good deal about the complex and obscurely intricate inter-relationships between sex, gender, identity and sexual orientation in individual Russian women’s lives.

First of all, Durova’s and Botchkareva’s histories differ in four major ways: There are obvious differences in class background (provincial nobility versus the peasantry); historical period (early 19th versus early 20th centuries); education (educated versus semi-literate). These two Amazons’ respective motivations for becoming warriors also differ: Durova, in fulfilling her military vocation which originated in her childhood, became what she was (or believed herself to be) and what Fate had pre-destined for her; Botchkareva, by her own account, was motivated by patriotic feelings to fight for her mother, Russia, in which, perhaps, she had unconsciously channeled her thwarted desire to protect her long-suffering and abused biological mother. Thirdly, Durova and Botchkareva come across in their accounts as markedly different personalities although it is very difficult to draw any conclusions from the tone of their respective narrations since the narratives themselves differ so fundamentally. Moreover, there is no way of knowing how, or how much Isaac Don Levine may have changed Botchkareva’s oral autobiography, consciously or unconsciously, in taking it down and translating it. Durova’s text allows for more rigorous analysis if only because she was a professional writer and in control of what she wrote and permitted to be printed.

The above caveats notwithstanding, Durova projects a cool, reserved, apparently ironic autobiographical persona while Botchkareva is ebullient, earthy, and apparently without guile as the central character in her full-length life story. Finally, Durova and Botchkareva, while initially in conflict over their decisions to enlist in the military and transgender themselves in order to do so, locate the source of their conflicting desires in very different inner (spiritual) considerations. Botchkareva tells us straightforwardly that when she had decided to enlist in the army in Tomsk, she felt torn between two mothers, so to speak: her own mother, who did not want her daughter to leave home or become a soldier, and Mother Russia, who, Maria felt, needed her to contribute to the war effort. Durova’s conflict is never pinpointed but seems to have involved the tension she encountered from a young age between the confinement of a woman’s traditional role that was rewarded with an open and socially approved life and the freedom to live as one chose, which, if one were a woman, could be gained only at the price of alienation, secrecy about one’s feelings and goals, and possible social ostracism.

Despite these important differences, the similarities between Durova and Botchkareva are noteworthy and perhaps more important in a larger cultural context if only because the similarities between two so obviously different Russian Amazons from two different periods in Russian history suggest the cultural roots, durability and broad compass of traditional Russian gender-role stereotypes. To begin with the personal qualities that Durova and Botchkareva share: Both women show a sincere enthusiasm for war, for taking an active role in fighting, a role almost universally viewed, under conditions of patriarchy, as quintessentially masculine. Accompanying both women’s virile martial spirit and indeed, one expression of that spirit is their deeply-rooted fighting patriotism. Neither one could express her patriotism in the supportive, home-front or rear-guard roles traditionally considered appropriate for women in war time.