In Rozanov’s opinion the distinguishing characteristic of a heterosexual couple (a male and a female) is oppositeness; therefore the most heterosexual couple is the pair in which “the female is the least male-like and the most female and the male is the least female-like and the most male. Pallas Athena, warrior-woman and wise woman, is not married, not a mother, and generally very little female. She has no age; she did not know childhood, shall not be a grandmother” (Rozanov, 36-37). For Rozanov, then, the male-identified and armor-wearing goddess Athena, patroness of Athens and its foundational culture and civilization exemplifies the eternal spirit (or archetype) and status of the Lesbian-Amazon: warrior woman and ageless non-mother.

Rozanov attaches gender significance to just about everything in his metaphysics. For example: he opposes a tree to a flower as male to female: “He is a tree, and lacking a scent; she is a flower, always giving off scent, even from faraway. As are souls, so are organs!” (Rozanov, 38). Rozanov argues that because Christianity as a religion and system of ethics stifled sexuality, European philosophers and writers were effectively prohibited from compiling information and “interesting facts” about sexual matters. They left this secret area of human experience and culture to “the dirty medicos”: They “who were used to roiling in all kinds of excrements, filth, illnesses, impurities, who lacked the fastidiousness to shun anything, did not shun sexual matters, either” (Rozanov, 39).

While Rozanov perceives the world and everything in it in terms of the male-female binary opposition, he also argues that femaleness and maleness are not absolutes. In human beings these categories are present in greater or lesser degrees. The more female a female is, the higher her plus-factor of femaleness; conversely, the more un-female a female is, the higher her minus-factor of femaleness. At the same time, the more plus-female a woman is, the more intense is her desire for sexual coition with her male opposite. Rozanov affirms a plus-and-minus scale of femaleness that runs from +8 to +/- 0 and from that mid-point down to -8. Plus-8 females desire sex with males the most and minus-8 females desire sex with males the least. Females who constitute the +/- 0 type on the scale provoke Rozanov’s special scrutiny: “Such females are not (sexually) dead although they absolutely never want. They have in them a certain + element, but it is connected with a certain – element. Therefore, they manifest no uni-directed attraction to the male; it is as if they are divided between two directions, one pointing to the male, and the other? The law of progression and the fact that all here is a matter of only two sexes indicate that the other direction can be pointed only to a female. A female seeks a female” (Rozanov, 49). According to Rozanov’s theory of female sexuality, female same-sex attraction and love is born quite naturally in one female’s search for her likeness, another female.

Two things require comment here. First, since Rozanov’s +/- 0 female by definition never “wants,” her searching mechanism must exclude sexual wanting, yet Rozanov describes the way she searches as analogous to the plus male’s and plus female’s wanting of their respective opposites. Second, as Rozanov develops his description of the +/- 0 female’s search for a female, it becomes clear that she is not looking for another +/- 0 female like herself. Furthermore, in her search she is more often stymied than not. However original and even “lunar-friendly” Rozanov may suppose himself to be, he is not original enough to conceive and propose the truly revolutionary idea of female same-sex desire. Rather, he lapses into the ho-hum notion that desire is by nature male, and even non-desiring or asexual seeking by a +/- 0 female must a priori bespeak a male component: “In the first female [the seeker—DB] this means a male too is present: but for the time being he is still so weak, barely born, that he merges utterly with the remains of the female as a female in the process of disintegration, who, however, is also merged with the male who has been engendered here. ‘Neither one, nor the other.’” (Rozanov, 49).

Rozanov’s newly engendered male will eventually rise, however feebly at first, from the female remains, and his theory of how his “lunar” (homosexual) woman develops begins to show its indebtedness to Otto Weininger, whose work Sex and Character caused the inevitable sensation when it first appeared in Russian translation in 1908. Rozanov’s lunar female ends up with a striking resemblance to the stereotype fashioned by the “dirty medicos” he claims to despise, namely the so-called mannish lesbian as male manqué. Here is Rozanov’s description: “A terribly rough voice, semi-male manners, she smokes, inhales and spits, speaks in a bass. Her hair is unruly, ugly and she cuts it short: ‘no braids for her’; she’s not really a girl, but some sort of ‘guy’. Where is there a hint of the “eternal feminine” here? …No, that’s not applicable to a woman like that: She takes courses, goes to political meetings, argues, curses, reads, translates, compiles…” (Rozanov, 49).

Therefore, Rozanov discerns Nature’s female same-sex seeker in a number of culturally identifiable women from the late nineteenth century and early twentieth who had recently become visible in what had been wholly male professions and endeavors: These women included Russian feminists, political radicals, readers, translators, compilers, professionals, wage-earners other than prostitutes, etc. For Rozanov such women could or do evoke from men the exclamation, “’God save me from marrying a woman like that!’” And he goes on to conclude: “And instinctively they do not marry them (despite marrying foolish, plain and downright ugly girls instead), for truly, ‘What kind of a wife would she be?’ … ‘ Not a Madonna, but a staff-captain.’ And she hardly needs a husband, she’s bored in his company, …A man, ‘soldier and citizen’ (the male direction/orientation), – is already half-awakened in her. And she doesn’t know how to wear genuinely feminine clothes. And men do not like them. But women do begin to like them: What a great pal that Masha is… The whole ‘mysterious female thing’ – keeps on exciting and attracting them inexpressibly, more and more intensely, until it torments them… the fact that it is all closed to them forever. … The torments of Tantalus: fulfillment eternally postponed [shades of Baudelaire’s notorious “damned women” – i.e. lesbians – femmes âpres i stériles—DB]; fulfillment is impossible, it shall not be, – ever! …’A staff-captain in a skirt’” (Rozanov, 50-51).

Interestingly enough, Rozanov finds a Russian fictional model that illustrates his theory of female same-sex attraction in Leo Tolstoy’s novel, Resurrection (1899), the heroine of which Katerina Maslova, a former prostitute (and therefore, one of Rozanov’s plus-female females, the most plus of whom are temple prostitutes), falls in love with one of her prison comrades, Marya Pavlovna, whom she loves with a special, exalted (non-sexual) love. Rozanov is struck by how close Tolstoy comes to describing the crux of female same-sex love when he (Tolstoy) writes of Marya Pavlovna, “‘Her own beauty delights her, but male attraction frightens her.’” (quoted by Rozanov, 104-105, n. 3). As far as Rozanov is concerned, Tolstoy’s Marya Pavlovna embodies the goddess Artemis, huntress of the forest and goddess of the moon: “And she is the whole type – of the Greek Artemis (goddess of the moon), the huntress wandering through the forests. But ‘beauty that delights’ clearly must delight some one because otherwise some sort of onanistic aesthetics would be involved. Whom does her beauty delight? Well, girls, women, of course! Marya Pavlovna did not quite succeed in hitting the bull’s eye just as Artemis did not. A step further – and the poetess Sappho of Lesbos would have resulted. Artemis represents an unfinished or more truly, transitional type in Greek mythology” (Rozanov, 104-05, n. 3). To state Rozanov’s unfinished conclusion: If Artemis embodies the virgin “lunar female,” Sappho (as Original Poetess in the universal lyrical pantheon) represents the sexual lunar female. It is telling that Rozanov avoids the word “lesbian” while making sure, through his reference to “Lesbos” that it remain unspoken on the tip of every reader’s tongue.

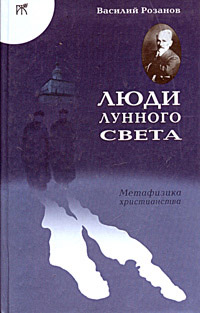

Yet, Rozanov’s main concern in People of the Lunar Light, is not human sexuality or homosexuality, but Christian metaphysics, however far afield his travels through Artemisian forests and brief stops on Lesbos may take him. The figure of Marya Pavlovna from Tolstoy’s novel brings him back to his central metaphysical theme because, as he understands Marya Pavlovna, her seeking if not desiring a female (Maslova), does fall short of hitting the bull’s eye of sexual fulfillment. For Rozanov, the goddesses Astarte and Artemis, and all +/- 0 females (i.e. celibate lesbians) embody metaphysical sexuality. They may suffer “the torments of Tantalus,” but like Marya Pavlovna they represent “the complete Christian woman” (Rozanov, 107, n. 2). Like early Christian women, Rozanov’s category of +/- 0 females is composed of females “whose vertical connections (with children and parents)” have been “metaphysically excised…and have been replaced metaphysically with thick outgrowths (in place of genitalia) used for ‘connecting with’ ‘intimates,’ ‘neighbors’ and ‘peers’” (Rozanov, 107).

In other words, Rozanov argues that Christian love is a kind of metaphysical intercourse practiced ideally by females or males who lack sexual desire for the opposite sex. The connection such celibate +/- 0 females establish with their intimates, neighbors and peers is “irreversible, implacable, indefatigable, not burdensome, and directly ‘nurturing,’ ‘satiating’ for female semi-sodomites…” (Rozanov, 107). Deprived of sexual gratification, Rozanov’s “female semi-sodomites” feed on charitable acts, nurturing ties with other people, mainly women, which compensate for the children, parents, and husbands who satisfy the needs of more plus-female females.

The above summary of Rozanov’s theory of female same-sex (lunar) love demonstrates the author’s dependence on the theories of homosexuality prevalent in his day in its failure to admit of sexual desire that is neither male nor phallo-centric and in its assumption that lesbians are either asexual or condemned to frustration and unsatisfiability. On the other hand, Rozanov does offer one or two genuinely provocative ideas about “lunar women” and “female semi-sodomites” that are unique to his writing on female homosexuality in the Russian cultural context. First, he recognizes the immemorial existence in culture and life of an autonomous type of woman, the Artemis type, who lives independently from connectedness to males and whose moral-emotional life is wholly woman-centered. Secondly, and more provocatively, he infers the existence in culture and maybe, life of a second type of lunar woman, the Sappho of Lesbos type, whose sexual as well as moral-emotional life is oriented to her own sex and who, by implication at least, can and does desire sexually and is able to satisfy her desire for another woman physically as well as metaphysically. What is new in Rozanov is not his admission of Sappho’s variant sexuality, which by 1911 had become a staple of French and other fin de siècle interpretations of the Lesbian poet. What distinguishes Rozanov’s theorizing of female homosexuality from other male theorists (such as his own most frequently cited medical source, Kraft-Ebbing) is his tacit acknowledgement that not all female-seeking females are celibate, sexually unsatisfiable and unsatisfied, condemned to fall eternally, tantalizingly short of “reaching the bull’s eye.”

Rozanov also articulates some rather radical ideas about sodomy, a term he applies to both male and female homosexuality in general as well as to a specific sexual practice (anal intercourse), ostensibly restricted to male homosexuals. The specific sexual practice, which he calls by the Latin term, actus sodomicus, disgusts him and he asserts his belief that it, as opposed to the more general, positive metaphysical same-sex orientation of sodomy, did not “in nine-tenths of all cases” (108) characterize same-sex relationships in the biblical Sodom. Thus, Rozanov falls one step short of stating that same-sex love excludes sexual activity entirely, and one can assume that the “female semi-sodomites” on whom he spends 99.9% of his narrative beg the question of the hypothetical “female full sodomites” who remain in the lunar shadows.

Rozanov does not discuss specific acts of female sodomy. He also does not put female-female (or male-male) sexuality on a par with male-female coitus. Instead, he speaks metaphorically of same-sex sexuality as a thermometer of sexual variation that possesses “myriad degrees” (108) along the scale to the (hideous) end-point of anal intercourse. Rozanov argues that the city of Sodom has gotten an unwarranted bad name in law, religion and even “objective science, only because the transitional forms tending toward sodomy have not been given their due, and sodomy itself has been understood not in terms of its psychology, talent and positive nature but under the pall exclusively of the single actus sodomicus, which in nine-tenths of all cases was not involved at all, and in the context of ‘spiritual partnerships’ even those accompanied by physical love, sometimes – of a sexual nature (here there were myriad degrees) that actus was absent in ten tenths of all cases” (Rozanov, 108).

Rozanov’s full definition of sodomy reveals a Platonic mind bent on idealizing the real and metaphysicalizing the physical. Sodomy becomes not so much a metaphor of Christian intercourse and friendship or love between humans of the same sex – although it certainly is such a metaphor – as an allegory of same-sex relations and connections of all kinds, sexual and non sexual alike.

From the above one concludes that Rozanov's theory of lunar love disassociates sodomy from any specific sexual act and tends to play down or circumvent any and all sexual aspects of same-sex love without, however, denying them. At the same time, he tends to oversexualize heterosexual relationships, appearing to reduce them to the practice of sexual coition for the purpose of species survival. In Rozanov’s lunar theory any kind of friendship or intimacy between humans of the same or opposite sex is in some part homosexual, or sodomistic. Anticipating by some eighty years the sodomy theorists of the 1990s, Rozanov affirms that “in essence all of life is suffused by sodomy” (109). Sodomy, even if it includes “the truly vile coitus per anum” includes it as “only one fiber, a single discrete ‘nerve,’ not a main or even significant nerve, in the boundless organism of sodomy as uncommon intimacy, as the penetration of one another by rays of light, as the probing of one another’s souls with heavenly probes, as love and finally, the quality being in love for individuals, both of whom possess the same genitalia” (Rozanov, 108). It is on the basis of his revised and enlightened understanding of sodomy (or lunar love) that Rozanov accuses medicine and the law of being too-narrowly focused on the genitalia and sexual practices of homosexuals while overlooking “the abundant fruits they have brought to the table of world civilization” (108).

But what do Russian “lunar females” themselves have to say about Rozanov’s theory of their attractions, love relationships and sexuality? Although nowadays, probably little, since People of the Lunar Light appears to have few readers outside of “a small group of Moscow dykes” (as reported by American sociologist Laurie Essig in Queer in Russia, Duke University Press, 1999), there are at least two Russian female poets of the 20th century, Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Barkova, whose writing and lives were affected by Rozanov in important ways.

A self-acknowledged bisexual, and in Rozanov’s terms, a lunar female, the great poet, prosaist and memoirist Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941) made perhaps the most original contribution to Russian lesbian theory and culture in her semi-autobiographical prose work, Lettre à l’Amazone, written originally in French in 1932 and revised in 1934. This work, as I hope to demonstrate here, reveals Tsvetaeva’s familiarity with and critical attitude to Rozanov’s People of the Lunar Light, which appears to have provided her with a springboard for jumping into her own theory of lesbian Amazons and their fateful “perfect unions.”

Lettre à l’Amazone (referred to henceforth as Lettre) was addressed ostensibly to the American-French lesbian writer Natalie Clifford Barney, to whom Tsvetaeva was introduced in Paris at the beginning of the thirties, and who earned the émigré poet’s enmity after losing a manuscript of hers which she (Barney) had promised to help publish. Lettre also tells (or retells) in encoded form the story of Tsvetaeva’s first physically consummated lesbian love affair, with Sophia Parnok (1885-1933), which took place in 1914-16, scandalizing and titillating Russian intellectual and artistic society in Moscow where both poets lived, worked and went to some pains to flaunt their “forbidden” passion. In my 1995 article, “Mother Nature versus the Amazons: Marina Tsvetaeva and Female Same-Sex Love” (Journal of the History of Sexuality Vol. 6, Number 1, July 1995) I have analyzed the autobiographical subtexts in Lettre as well as the work’s multifaceted significance for trying to understand Tsvetaeva’s complex attitudes to her own lesbian desire. Here I shall explore the Russian theoretical underpinnings of Tsvetaeva’s ideas on female same-sex love as expressed in Lettre, which continues to stand as the only original theoretical work on lesbianism by a Russian writer, one, moreover, with lesbian experience which enabled her to know personally what she was theorizing about. Specifically, I would like to demonstrate the several heretofore unnoticed implicit connections that exist between Tsvetaeva’s theory of Amazon (or lesbian) love and Rozanov’s theory of sodomy or lunar love.

After she had evidently read People of the Lunar Light, Tsvetaeva wrote Rozanov in a 1914 letter that the book illustrated his capacity to write “repulsively, … but never untalentedly” (Tsvetaeva, VI/126). Despite her revulsion at the book, she clearly came to agree with many aspects of Rozanov’s theory of lunar love and his ideas on human sexuality, in general. To begin with, Tsvetaeva sharply distinguished physical love (i.e. sex) from love itself (or spiritual love), privileging the latter as the only “real” love. She also believed that any kind of sexual love was incompatible with Christian love (i.e. the love of which Christ speaks), arguing in Lettre that it is unreasonable to condemn female same-sex love in the name of Christ because

A view such as the above on the incompatibility of sexual love with Christian love has an interesting effect on both Rozanov’s and Tsvetaeva’s attitudes to homosexuality. On one hand, they argue, albeit in different ways and via different examples, that true homosexual love necessarily bespeaks an aversion to sexual love as at best, a human affliction for which Christ is the cure; on the other hand, they put same-sex on an equal footing with opposite-sex sexuality – both kinds of sex are “equally, irreparably vainglorious,” as Tsvetaeva puts it. The equalizing of homosexual and heterosexual sexual love that one finds in Rozanov’s and Tsvetaeva’s writing on homosexuality effectively removes any special stigma from homosexuality and reminds one of the Russian Orthodox penitential texts on female same-sex “sins” that were discussed in chapter two. In Rozanov and Tsvetaeva as in the medieval penitentials, sex itself is the sin, not the orientation of the sinner.

Homosexuality has long been condemned as unnatural and excessively sexual, in part because of its non-reproductive nature. Rozanov, however, takes a different tack on the issue of naturalness because he views the desire to have children as a sexual desire, indeed the root of all sexual desire. Homosexuals / Lunar people, in Rozanov’s view are those who do not want children, in the case of females, women who “never want” carnally, who eschew physical motherhood and conjugal relations with men and who love, in the vast majority of cases, fully, but with little or no need for sex. (As has been pointed out, Rozanov cannot conceive of female same-sex sexual intercourse because it obviates phallic penetration).

On the whole, Tsvetaeva tends to agree with Rozanov as to the predominantly spiritual (soulful) complexion of lesbian relationships. She states that one of the partners in a typical lesbian pair, the one she calls “the older woman” though age is not an issue, is necessarily characterized by her lack of “an inner need” for children and desire for sex with men, and she also downplays the importance of sexual attraction in most female same-sex unions. Tsvetaeva argues that a female-seeking female is recognizable by her “soulful look”: “Young or old, these are the women who have the most soulful look about them. All other women who have a look of the body about them do not have their soulful look, are not of the same stuff, or have it only in passing” (V/495). Such a female “restless soul” does not need a child because her female lover is her child, her “everything,” she does not seek love in love and may seek only soul (her like). In looking for partners, Tsvetaeva’s “restless soul” practices a noble form of seduction – a version of Rozanov’s spiritual or metaphysical sodomy – in a kind of Nietzchean becoming of what she is, “a trap of the Soul” (V/492). Because the majority of women who fall into this trap have a look of the soul only in passing, and ultimately need a child (from a man) to satisfy their “inner need” they usually inevitably leave their same-sex soul-mate in order to get married “to the first male who comes along.” Therefore, Tsvetaeva concludes, the female-seeking female’s relationships are shortlived, though numerous, until she reaches old age. Then her innate pride condemns her to solitary celibacy. Only occasionally does Tsvetaeva’s true female-seeking female find a same-sex partner for life. Such lifelong female same-sex unions strike Tsvetaeva as both “moving” and “terrifying” because one such female couple seemed to her “surrounded by an emptiness more empty than what surrounds a normal, infertile old couple, an emptiness more isolating, more desolating” (Tsvetaeva, V/490).

Tsvetaeva does not follow Rozanov’s scale of plus-female females and minus-female females, but she does create categories of females who are exceptions to what she considers the normal-case scenario for female sexual development. Tsvetaeva’s normal case may strike many as a radical departure from the norm, however, since she defines it as “the natural and vital case of the young female who fears men, is attracted to women and wants a child” (V/489). She argues that a normal young girl would have nothing to do with the “enemy” male, and never has any sexual desire to couple with him, were it not for her inner need of a child. Tsvetaeva believes that heterosexual unions exist only to satisfy the normal young woman’s need for a child, and she must necessarily sacrifice the perfect unity of love she enjoys only with a female lover in order to satisfy this biological imperative. A reminiscence of Rozanov’s scale of plus and minus femaleness creeps into Tsvetaeva’s theory when she acknowledges that her normal female is “more she” (V/487) than women who qualify as exceptions to the normal case, that is, the women Tsvetaeva calls “Older Women” and “Others” (Rozanov’s +/- 0 females or lunar females).

In order to compensate for a lesbian couple’s inability to produce a child from each other, Tsvetaeva considers the possibility of adoption and imagines a time when artificial insemination will be possible: “Let’s assume that some day it will be possible to have a child without a him” (V/490). What she cannot imagine is accepting a substitute for the “natural” thing, the latter being, for her normal young woman in love with a woman “the desire for a child from her,” (488) “the desire ‘to love a little-girl you’” (486). Nor, ultimately, is Tsvetaeva willing to consider adoption a viable compensation for the biological daughter it is impossible for a normal young girl to have from her older-woman lover; such a substitution strikes her as pushing nature’s envelope too far: “It is not impossible to resist the temptation of a man, but it is impossible to resist the need for a child. That is the only vulnerability that undermines the integrity of the cause [permanent female same-sex unions—DB]. The only vulnerable point that allows the corps of the enemy [a man—DB] to enter. For even if some day we shall be able to have a child without him, we shall never be able to have a child from her, a little-girl you to love. (An adopted daughter? Neither yours, nor mine. With, in addition, two mothers? Better leave it to nature to do what she does.)” (Tsvetaeva, V/490).

Tsvetaeva’s insistence on the naturalness of biological motherhood and on the unnaturalness of adoptive motherhood and her unwillingness in this instance to overcome the constraints of physiology and think symbolically may reflect her own unresolved issues about her lesbianism and internalized homophobia as I have argued in “Mother Nature vs the Amazons. Marina Tsvetaeva and Female Same-Sex Love.” However, the poet’s personal fears about her own sexuality neither compromise the originality and cultural significance of her theory of female same-sex love, nor make her hostile to lesbian sexuality in general. She does not exclude the existence of long-term lesbian relationships and does not question their emotional and spiritual integrity. Nor does she consider the female-seeking female to be lacking in any way due to her desire and choice to live without men.

Although Tsvetaeva, following Rozanov, believes the origins of female same-sex love lie in spiritual and emotional attraction rather than sexual desire, and that sometimes, lesbian relationships lack a sexual aspect altogether, she does not agree with Rozanov that most female same-sex unions are asexual and wholly “metaphysical.” Tsvetaeva’s typical lesbian relationship as she describes it in Lettre begins as an intense friendship of soul-mates and develops into a sexual intimacy, which is wholly satisfying to both partners and in fact, a model of “perfect love.” Ultimately, however, the “more-she” of the two lovers will begin to desire a child more than she desires to love her woman-lover and will be forced by her inner need for a child to leave the relationship and marry “the first man she meets.” Tsvetaeva also agrees with Rozanov that the “less-she” women-loving women can live – even prefer to live – without motherhood, and when they are old, they revert to solitude and celibacy. Finally, like Rozanov, Tsvetaeva considers the most soulful women who live celibately with or without same-sex partners, to be the most nobly lesbian women.

In the end, Tsvetaeva believes the majority of females, what she calls “the normal case,” are basically bisexual women with a pronounced tendency to spiritual-emotional and erotically tender love relationships with other women. Such normal females, according to Tsvetaeva, have at least one full-blown same-sex love affair in their youth, which they leave for marriage and the male who will fulfill their intense inner need for a child, something they have dreamed of having since early childhood. In Tsvetaeva’s view, normal females are always too young for sex with males, but never too young for a child – that is why they initially fantasize about having their female lover’s child.

All exceptions to the normal case in Tsvetaeva’s typology of female sexualities are what Rozanov would designate (with one exception) +/- or – females. Tsvetaeva delineates five categories of non-normal cases: “The non-maternal woman (the exceptional case); the instinctually or fashionably depraved girl (the banal case); the restless female soul who seeks in love for a soul and is therefore predestined for a woman (the rare case); the great female-lover who seeks love in love; and the clinical exception” (Tsvetaeva, V/488-89).

The child-centeredness of Tsvetaeva’s theory of female sexuality greatly reflects the poet’s own matriphobia, the privileging of motherhood in Russian culture generally, and Russian notions of femininity in particular. Perhaps one reason the young Tsvetaeva found People of the Lunar Light “revolting” stems from Rozanov’s persistent elevation of a plus-female female’s desire for a male over her desire for motherhood in his delineation of the “eternal feminine.” In Russian culture, a non-maternal woman of whatever orientation is truly, as Tsvetaeva argues in Lettre “the exceptional case.”

For Tsvetaeva’s and Rozanov’s intellectual generation, the non-maternal woman may have been socially acceptable as a so-called new woman, but she still was atypical enough to be considered not normal by her peers, at least in the privacy of their own homes. Moreover, the non-maternal woman was easily conflatable in sophisticated urban society with mannish women and lunar females. Such blurring of sexual orientations and professional and behavioral ways of life and manners among women and society’s view of them in post-1905 Russia is illustrated in the case of the poet Anna Barkova (1901-1976), who led an exceptional, many would say exceptionally tragic life. A genuinely working-class intellectual and poet, a true believer in the new Communist society, the innocent victim of Stalinism who spent scores of years in labor camps and exile for no crime whatsoever, Anna Barkova, whose previously forgotten work came to light in the early 1990’s as a result of glasnost, was a lesbian (or as she called herself, “a lunar person”) and a non-maternal woman. Improbably considering her background, education and politics, Barkova found a name, theory and justification for her sexuality in Rozanov’s People of the Lunar Light.

In her Notebooks for 1956-57, Barkova writes: “In regard to sex and marriage he (Rozanov) is certainly correct. I realize that. But as a person “of the lunar light” I find his correctness damned annoying” (Barkova, 366). Judging by the fragmentary and typically metaphorical, though unflinching recollections of her own emotional and sexual development that Barkova records in her Notebooks, she seems spontaneously to have followed Rozanov’s theoretical model for the +/- 0 female. The glimpses she provides of her sexual development also call to mind, often uncannily, Tsvetaeva’s theory of both the normal-case young girl and her Other Woman. At the same time, Barkova departs significantly from Tsvetaeva’s normal-case scenario for female sexual development in that she (Barkova) had no interest in children or in having them. Yet, she clearly saw herself as no less female for being totally non-maternal. As far as one can tell from her writings, Barkova expressed no identification with males; indeed, in one poem, “In a collective grave-pit, coffinless” (1953), where she imagines with bitter sarcasm what a future philologist will invent about her life, she asserts proudly: “But in your nasty vinaigrette / My reader shall not find me. / After death they wrote down my sex as male… / I was always, my whole life a she” (Barkova, 94).

This bold, uncategorical affirmation of femaleness from the Amazon’s mouth, so to speak, shows that Barkova was aware of her culture’s tendency to masculinize childless, single, lesbian women, and view them as men manqués. Barkova’s female self-identification also suggests her desire to affirm the femaleness of everything she was: poet, martyr, Amazon, lesbian.

Barkova was born and grew up in the textile factory town of Ivanovo outside Moscow where her father worked as a janitor at the Gymnasium. This afforded Barkova the opportunity for an education that a woman of her time and social class would normally not have had. Barkova’s diaristic writings tell us little about her early life apart from her comment that “from earliest childhood I sensed threat and destruction in the sexual. From the age of eight my one dream was of greatness, glory and power via creativity of the mind.” Then, in a startling confession for a Russian woman, Barkova notes her negative attitudes to maternity and marriage: “I didn’t like children and don’t like them to this day, and I’m now 55. And when I had a dream that I was getting married, in that dream I was seized with inexpressible horror, a feeling of enslavement” (Barkova, 367).

Had Rozanov caught a glimpse of the young Barkova, he would have remarked ironically, “’Where is the eternal feminine here?’”. But Barkova instinctively saw eternal femininity as enslavement. She feared the sexual as destructive to her Amazonian femininity and the power of the goddess Artemis it confers. For this reason, in her early poem “Sappho,” Barkova rejected sexuality: “For I am hard and warlike, / And know not amorous woe.” (Barkova, 22). The Amazon persona in Barkova’s early poems has much in common with the Older Woman type Tsvetaeva theorizes in Lettre. Yet, Barkova’s lyrical I enforced celibacy on herself out of fear of the weakness engendered by sexual love – “I fear the infection of weakness,” she states in “Two Women” (1921) – while Tsvetaeva conceived of the lesbian Amazon as a seductive femme fatale, especially for young, virginal girls.

Barkova’s first consummated love affair apparently came late in her life, during her last imprisonment in GULAG, and she celebrated it in her late verse as a mixed blessing. The poet’s ambivalence can be explained in part by the horrible surroundings in which the lovers found themselves:

The sad irony of her sexual life was not lost on Barkova: In youth she rejected sex from fear of the metaphoric chains that sexual intimacy portended to her; when she finally experienced sexual love, in late middle age, it liberated her metaphorically (and creatively), but taunted the real chains that bound her and her lover. At the same time, one notes how the course of Barkova’s sexual life reverses the chronology of the typical Older Woman lesbian hypothesized by Tsvetaeva in Lettre. Tsvetaeva’s theoretical Older Woman lesbian (or lunar woman) leads a sexually active life only so long as she is young; then, her pride gives her no choice but to reject sex altogether in old age and retreat backwards into her true self, a solitary celibate “mountain” of a woman. Barkova’s pride and fear of sex gave her no choice in her youth but to embrace celibacy, but in her “ugly” old age she gave into her desire and allowed herself to be loved: “As a rotting crust is loved / In monstrous times of famine, – / So I am loved and kissed / On my dark blue and crusty mouth.” (“Me,” 1954; Barkova, 128)

Barkova acknowledged that her pride was “much more intense than the norm” (Barkova, 364) and constituted a part of her “dark side” that counterbalance the “sparks of genius” she was sure she possessed. Pride probably underlay her rejection of sex. Her first experience of sexual desire coincided with her belief that the “love” she felt “was hopeless, – it was absurd to expect anything to come of it.” She recalls her experience of first love in one of her prose works (“Time Found”) and considers it the model for her late-in-life love affair: “I was only 13. I was a high school student. And I was in love with a woman. She, of course, was much older than I. She was my teacher and a German. I was Russian. And the so-called ‘First World War’ had been going on for about a year already.” (Barkova, 378). It is noteworthy that Barkova sees the main hindrance to sexual consummation of her first love as not the same-sex nature of her desire, not the age difference between her and her object of desire, not the student-teacher relationship between them, but the fact that their respective nations were at war. She apparently believed in looking back that her early teenage love was hopeless mainly because she was Russian and her teacher German. Leaving aside the apparent disingenuousness of Barkova’s self-analysis, I think it is important to emphasize the connection between her vow of celibacy and her recognition of the hopelessness of her love due mainly to the fact that her love challenged if not sexual, then patriotic conventions.

When Barkova finally read Rozanov’s People of the Lunar Light, the philosopher’s belief that “lunar females” suffer “the torments of Tantalus,” i.e. endlessly postponed sexual satisfaction, must have resonated within her. (Of course, it is always possible that Barkova constructed her memoirs of her first love on the lunar-female model provided by Rozanov.) It was mainly to avoid such torments that Barkova developed the (not uncommon) type of pride that keeps people who possess it from even trying for things they believe it is impossible for them to obtain. For a person with Barkova’s will to power and apparent obsession with the question, “Isn’t there in love an instinct for power?” (Barkova, 376), this would be even more likely. Far better to be a cold, celibate woman than a passionate, weak one. As Barkova comments in her diary: “A lot of inner tolerance is needed to get along with another person and not come to hate him. Any monastery is where I can live best. Is that a plus or a minus? Flexibility or weakness?” (Barkova, 355)

It must have been Rozanov’s insistence that most lunar relationships are celibate and therefore closer to the Christian ideal of spiritual love that attracted Barkova to his theory of lunar love and led her to grapple with him intellectually as seriously as she does in her diaries. She expresses empathy with him as a victim of the sort of irony she recognized at play in her own life: “Rozanov was not fond of laughter, but life, albeit posthumously, made mercilessly demonic fun of his cherished ideas and sexual insights.” (Barkova, 366) Not only does Barkova find Rozanov irritatingly correct about sex and marriage in general, she appreciates his belief in “the mystical and metaphorical quality of the sexual act among all animals. The fact of the sameness of physical intercourse in animals and humans,” Barkova continues, “exacerbates one’s extreme repugnance for the world of sexual love; and that world is extraordinarily broad and many-sided. But the foundation is one and the same” (Notebooks, 264). Barkova concludes that only the instinct for power and the “creative instinct” “distinguishes humans from our four-legged brothers and…perhaps both these instincts are merely the product of the sexual instinct,” a fairly widely received truth she claims to have guessed at the age of fifteen.

In addition to identifying herself as “a lunar person” of the Rozanov type, Barkova acknowledges possessing a Nietzschean “insane desire for self-affirmation, creativity, power over another’s soul, a desire to change the world – all of which are sad, anti-social, criminal qualities” (Barkova, 377). Here, as elsewhere in her writing, it is hard to tell whether Barkova sincerely nurtured such grandiose feelings about herself in relation to other people and found the language to express them in the high-powered books she read and only partially digested, or whether she reimagined herself in terms of the human types delineated by the authors of those books as a way of concealing her true self in them. On the whole, Barkova emerges from her notebooks as an acerbic, tough and ironic person who is distrustful of people, proto-fascistic and openly anti-semitic:

One notes in passing that such fascist leanings have been observed in the political views of several well-known European lesbians of the 1930’s and 1940’s, such as Radclyffe Hall, Una Trowbridge, Natalie Clifford Barney and Vita Sackville-West, although in the case of those mentioned ring-wing sympathies sat better than in the proletarian Barkova with the women’s wealth and aristocratically conservative worldviews. Barkova’s anti-semitism, which flashes here and there throughout her memoiristic prose, becomes blatant after her break-up with Valentina Makotinskaya, her lover of many years and a Jew, in whose character Barkova came to discern “the great minuses of Jewishness” – “a gift for betrayal,” “in-born lowliness,” “two-facedness” (Barkova, 367).

Barkova’s bitterness, her lack of belief in anything and her tendency to value only people like herself who had spent long terms in the GULAG, convey a Céline-like view of the world which Barkova herself seems to be aware of: “What do I myself believe in? In nothing. How can one live that way? I don’t know. I live by the most atavistic instinct for survival and out of curiosity. What they call journey to the edge of night” (Barkova, 358). Despite the note of a too self-conscious Dostoevskian Underground Man that sometimes sounds from Barkova’s narrative voice, she makes an original contribution to the well-represented genre of Russian camp-survivor memoirs. Unlike most such memoirists, Barkova can find nothing positive to say about her long and unjust imprisonment, nothing positive about the actual physical conditions she suffered (in this she speaks for almost all ex-zeks), but also nothing positive for her spiritual and moral development (which differentiates her from many camp survivors). Barkova’s view of life, tempered by twenty years of GULAG, is unremittingly dark, bitter and ironic, at times almost intolerably so. Even the great, spiritually uplifting love that she found in prison – which she calls her “savior” – she perceives as having happened despite, not because of her incarceration.

Barkova’s poetry encompasses a significant number of poems on lunar themes, including love lyrics, the strongest of which are the poems she wrote to and about her lover Valentina Makotinskaya, her sister prisoner in Komi. Although Barkova does not usually emphasize the femaleness of her lyrical heroine’s object of desire in her love lyrics – she avoids the intimate “thou” (ty) form of address, which would mandate grammatically feminine inflexions, using the grammatically ungendered “you” (vy) form instead – her poems are sufficiently “lesbian” to a Russian reader to require the following sort of justification for their sex-variant contents from a recent Russian critic, Leonid Taganov, in a 1990 critique of her work: “She foresaw negative criticism in regard to the non-conventionality of the human relationships that are recorded in her love lyrics” (Barkova, 489). That sentence unintentionally conveys a lot – at least to a western reader – about the status of and attitudes toward lesbians in post-Soviet Russia. Taganov titles his article on Barkova and her love lyrics, “Sappho in Hell” (cf Mikhail Safonov’s article on Dashkova, “Princess Sappho? Antique Passions on the Banks of the Neva,” discussed in the previous chapter), which suggests that the critic’s polite circumlocution in calling Barkova’s lesbian relationships “non-conventional” human relationships does not exclude his equally polite exploitation of them to attract readers.

Of all the poets that have been dubbed Sappho in the history of Russian literature, Barkova, who unlike most of them was a lesbian, is ironically least appropriately named Sappho, if only because she rejected the poetic identity of the Lesbian poet for herself. Her lack of sympathy for Sappho as a poet of love may have been one factor motivating the disdain she expressed for her older lesbian contemporary’s (Sophia Parnok’s) collection of Sapphic imitations, Roses of Pieria (1922), in her brief review of Parnok’s book: “It is not worth reading these sweet nothings, but if anyone does read them – let him, the writer writes, the reader reads – that’s the formula most applicable to this sort of literature” (Barkova, The Press and Revolution, 1923, No. 3, p. 264). Ironically, too, one can find more than a hint of Parnok’s lyrical manner in some of Barkova’s late lesbian love lyrics, especially the 1976 “Forgive my night-time soul,” written shortly before Barkova died. The simplicity of feeling and diction, prosaic intonation and conversational rhythm in this poem are all reminiscent of a poem like “Silver Gray Rose” in Parnok’s cycle, “Useless Goods,” which also concerns the poet speaker’s feelings of sweet despair in her late-middle-aged (and last) love affair. One wonders if Barkova might not have heard, or even read in manuscript, Parnok’s late unpublished poems that circulated in Moscow underground lesbian circles in the 1970’s.

Taganov makes an interesting comparison between the poetic profiles of Barkova and Tsvetaeva although he merely hints at a shared sexual orientation and says nothing at all about the relevance of Tsvetaeva’s lifelong interest in Amazons and theory of female same-sex (Amazon) love to Barkova’s life and poetry.

In an unfinished long poem, “The First Woman and the Second Woman [Barkova herself—DB]” (1954), Barkova pinpoints the thrust of her lyricism: “And in her art the whole point was / Irony and spiteful cynicism” (Barkova, Selected Poems, p. 81). Elsewhere in this poem, which employs the romantic meeting of two inmates (Barkova and her lover) in a labor camp as an occasion for the poet’s moral and political meditation on life in Soviet Russia, Barkova compares herself to the persecuted and imprisoned British homosexual poet Oscar Wilde: “To Wilde’s woeful lot / Was she at last condemned” (Barkova, ibid.) Barkova’s identification with Wilde expresses the connection she apparently saw between her homosexuality and her political fate.

For the most part, and true to the conventions of Russian and Soviet society where the personal is never political, or openly admitted to be so, Barkova gives little indication that her “ironic and spitefully cynical” poetry was in any way related to the “woeful Wildean fates” of lesbians in her lesbophobic society. However, some of her poems do communicate her awareness that her status as a “lunar person” like other of her idiosyncratic tastes and beliefs, did affect what she chose to write about and therefore, her homosexuality could be argued to have a political aspect. For example, in the 1953 poem “Hafiz” (the name of the medieval Persian poet whose lyrics on wine, man-boy love and song made him a gay icon for Mikhail Kuzmin, Sophia Parnok and other lunar artists during the fin de siècle period in Russian culture), Barkova speaks of the fact that unlike “old man Hafiz” she cannot write openly of the “amusing caprice” she secretes in her soul: “An amusing caprice lives in my soul, / It I do conceal. / And what old man Hafiz has told, / I do not dare reveal” (Barkova, 96).

In the previously mentioned “Sappho in Hell,” Taganov cites Barkova herself to substantiate his view that she was all too aware of the negative political implications of being in a lesbian love relationship and living with the constant fear and terrifying thought “that [one’s] poor happiness will be crushed by a mob of dull-witted and savage people.” “Barkova knew,” continues Taganov, “that now or later people would hurl mud at [her] love” (Barkova, 489). If Barkova was correct that her love for her own sex would inevitably incur mudslinging in her peer group, then that provides additional support for the poet’s decision earlier in her life to forsake the blandishments of Sappho, “the passionately-coiffed priestess of love,” in order to gird her Amazon loins with the cold freedom she loved.

Unfortunately, Barkova’s at times transparent delight in self-dramatization, her vaunted will to power in love and her persecution mania – many lines in her poems sound like versified versions of the self-analyses of Dostoevsky’s underground man – make her at best a prejudiced witness to the political and social negative sanctions and penalties that lesbians suffered in Soviet Russia. Olga Zhuk’s recent study of the lesbian subculture in the GULAG shows that lesbian relationships and even so-called families were widespread in the camps as well as an open secret that was more or less tolerated and hardly incurred inevitable condemnation or punishment. On the other hand, Barkova’s perceptions are obviously sincere and represent the reality she experienced in Abez. Her ever-present fear of being suddenly separated from her lover, due to the total unpredictability of a camp inmate’s life, has been testified to by other women in same-sex couples. For example, in her memoir Together with Alya, Ada Federol’f movingly describes her constant fear of being separated from her beloved Ariadna Efron whenever transports took place (and this was when she was living in exile, not in a camp where no freedom at all existed): “At that time any change of place, any possible separation seemed to be the most frightful thing. We wanted to grow into our perhaps poor, hungry and cold life, but life in our own corner, and mainly, life together” (Federol’f, 243). Or, another example: “I was afraid that Alya and I would be separated. After all, we had just seen how they divided the transport in Turukhansk” (Federol’f, 234). Because of the ever-present threat of secret police spies denouncing ex-prisoners, Federol’f also notes the constant pressure for her and Alya to live as anonymously as possible: “It was crucial to live very unobtrusively without attracting attention” (Fedrol’f, 260).

The issue of not being able to speak freely is not restricted in Barkova’s work to the context of the poet’s sexual orientation. In the poem “Film,” Barkova makes the general political point that it is impossible to speak honestly about anything in Soviet society because the whole culture officially demands that all writing have a lofty educational goal and tone, as if written for schoolchildren, even though no one pays attention to the lessons the writing aims to teach:

A writer who does not want to participate in this sort of hypocritical writer-reader communication, has no choice but to maintain silence on certain subjects. Among the subjects about which Barkova believed it was best to be silent was love, love which the speaker in “Film” calls “my saving ark.” At the time the poem is being written, however, her ark has been marooned “on some Ararat” and the poet does not know which one:

Despite the occasional hints in Barkova’s poems that her lesbianism played a role in the political persecution and social ostracism she suffered, the main political thrust of her poetry has nothing to do with her self-proclaimed lunar identity. Rather, her embittered and ironic voice resonates with the profound disillusionment of a disenchanted true believer in Marxism as it exposes the ruthless injustice of Soviet power that crushed the poet and millions of others like her. The political system Barkova believed in ended up ruining her life. The poet speaks directly of her disillusionment in “The First Woman and the Second One”:

More important than the political aspect of Barkova’s poems in distinguishing her voice as that of a Russian lesbian poet are the ways she identifies her poet speaker in her lyrics. The constantly changing lyrical personae in Barkova’s poems are noteworthy for the variety of lunar female identities they embody. A random selection of Barkova’s non-love and love lyrics from the collections The Return and Selected Poems (encompassing poems written from the early 1920’s, the early 1950’s and the mid-1970’s) shows the wide range of identities adopted by the lyrical heroine (the I in the poems). She calls herself variously: an exiled woman, a tigress, ancient wine, a nun, a sensitive monster, a witch, she, the second arrested woman, Oscar Wilde, a dry, boring woman, I, a piteous fortune-teller, Red Army woman, a female criminal, a priestess, your dare-devil child, an Amazon, Amazon-Rebel, a frightened child-woman, and a leper woman. In addition, she emphatically dis-identifies with Sappho.

As a group, Barkova’s lyrical heroines loudly and clearly affirm the poet’s female self-identification. Within the cultural context of early-twentieth-century theories of lesbianism, Barkova’s insistence on her femaleness runs counter to the prevailing view that true female homosexuals are more “masculine” than so-called normal females. At the same time, several of Barkova’s lyrical personae represent traditionally constructed and perceived code names for lesbians in European and Russian literature and culture, e.g. Amazon, Amazon-Rebel, witch, monster, leper, Red Army Woman (pace Maria Botchkareva), even not Sappho. Although the lyrical heroines of most Barkova poems, when read separately, hardly can be said to announce the poet’s lesbian orientation, a list of them all conveys a different message, or rather, a message of the poet’s difference from other female lyricists. Clearly, Russian readers must sense this difference. If they did not, there would have been no need for Leonid Taganov by way of re-introducing Barkova to the Russian poetry-reading public to write the following justification of his interest in Barkova and his desire to quote generously from her love poems:

For Barkova herself, the most telling aspect of her lyrical personae is the considerable amount of self-hate they express and the ambivalence they convey about the poet’s experience of herself as a lunar person. It is clear Barkova paid a high price for the love she forswore, the fear of sex she nurtured in herself, and the cold freedom her vow of celibacy, will to power and monastic bent required. In the final stanza of the 1921 poem which begins, “Cold freedom is what I love,” the speaker acknowledges the double-edged quality of her words and reveals the fissure between mind and heart that bifurcates her lunar self: “I speak with two-sided words / I, the Amazon-Rebel, / While my heart cries secret tears / Of a frightened woman-child” (Barkova, 26).

Trying in life to realize the theoretical ideal of Platonic and Christian lunarity that Rozanov argues for in People of the Lunar Light, and adopting Rozanov’s “lunar person” to name her “un-namable” variant sexuality, Barkova spent the free years of her life consciously stifling her “sexual instincts” in order to ensure and enhance her freedom, power and creativity. Only when she had lost her freedom and become a powerless victim of the Soviet state, did she give into the sexual feelings she had repressed for years. Her submission to love for another woman empowered her “creative instinct,” yielding her love poems to Valentina Makovinskaya, some of the best poems Barkova wrote.

In some ways Rozanov’s theory of female same-sex love can be seen to have had an opposite impact on Tsvetaeva. I would argue that the ideal of Platonic lunar love Rozanov articulates may have provided the male-identified, nominally bisexual (but for the last 15-16 years of her life, apparently celibate) Tsvetaeva with an authoritative theoretical basis for justifying the repression of her lunar female sexuality. Sexual and other forms of repression seemed to energize and empower Tsvetaeva’s creativity as forcefully as the loosening of her repressed sexuality empowered Barkova’s.

At the beginning of Lettre à l’amazone, Tsvetaeva speaks about renunciation and repressed desire, specifically, considering the addressee of her remarks, her lesbian desire. She creates an erotically charged metaphor for the renunciation of desire by comparing renunciation to “having everything to say and not opening one’s lips,” “having everything to give and not unclenching one’s fist”

The fetishistic, transgressive eros that permeates Tsvetaeva’s writing and as Taganov correctly points out, seems to lend “everything the poetess speaks about” an existence “in the intensely erotic space of her poetry,” derives from the “springboard of denial” that energizes all Tsvetaeva’s actions. Eros that is constantly and consciously renounced cannot help but be transgressive whenever and however it is expressed.

Rozanov’s theory of lunar love provides a Russian philosophical soul-mirror which enabled two very different 20th century “female-seeking” female poets, Tsvetaeva and Barkova, to see reflected the outlines of their innermost lunar identities. Those lunar identities differ in many ways yet present beguiling contiguities, revealing thereby a common cultural model.

Despite her marriage and motherhood (to three children, one of whom died in infancy), Tsvetaeva represents her self in her poems and epistolary fantasies as a near-perfect embodiment of what Rozanov calls the plus/minus 0 female and what Tsvetaeva herself views in different guises as the bisexual Amazon-Poet, the Devil’s little girl, a Tsar-Maiden, Bride in an Armor of Ice, Mountain’s daughter, and a Persephone reclaimed from Hades for Lyricism. Tsvetaeva renounced her sexuality in order to be her Genius’s bride and a powerfully autonomous magician of the Word. She wanted nothing less than divinity, godlike creative power.

Tsvetaeva’s emotional disposition and physical appearance were boyish (at least in her youth) and she nurtured the fledgling male spirit she desired to rise from the ashes of her hated female body. Tsvetaeva repeats throughout her writing that she does not like love. She championed the friendship of souls eternally and creatively bonded against the ravages of Eros. Like Rozanov’s “spiritual companions” Tsvetaeva’s ideal partnerships were Platonic same-sex intimates like the mythical Orestes and Pylades or eroticized materno-filial dyads like the mythological Demeter and Persephone. The one aspect of Rozanov’s theory Tsvetaeva did not support was his idea that lunar females have no need for maternity. She believed that motherhood was an innate need for almost all females regardless of their sexual orientation. She also perceived maternity as virile (and her own femininity as “manly”).

As a true metaphysical lunar person, an Astarte or Artemis, Tsvetaeva, one imagines, would have been content to avoid sex entirely, create poetically, recreate parthenogenetically and nurture her life-long yearning for chastely erotic same-soul relations with women and lunar male poets. And she came close to realizing her Amazon ideal in her personal life: Aside from two brief but intense sexual intimacies (with Sophia Parnok and Konstantin Rodzevich), and the initial period of her marriage to Sergei Efron, Tsvetaeva seems to have led a celibate life, renouncing her desire for sex while permitting herself the transgression of writing.

Barkova’s life reveals another relation to Rozanov’s theory. Like Tsvetaeva, she aspired to chaste Amazonhood and consciously rejected love. Unlike Tsvetaeva, she was “always a she” and despite the superficially masculine qualities her lyrical heroines appear to have, she saw herself as wholly female. Unlike Tsvetaeva as well, she had no doubt about her lunar identity. Indeed, Rozanov’s greatest importance to Barkova was in providing and authoritative, if irritating theory and language through which she was able to articulate what and who she was. (Here it is important to note that Tsvetaeva and Barkova are unique among Russian lesbian writers in actually affirming a female same-sex affiliation, if not identity, for themselves. Even Sophia Parnok, whose lifestyle was more openly homosexual and whose poetry is more markedly lesbian than either Tsvetaeva’s or Barkova’s, never affiliated herself in writing with a lunar or lesbian orientation. The closest she came was her frank admission to a male friend in a private letter that she “had never been in love with a man” by which she meant to imply that she had been in love with women.)

Barkova’s diaries, fragmentary, restrained and written through the haze of memory as they are, nevertheless provide glimpses of a recognizable early 20th century lesbian girlhood and adolescence in Russia among the working class. It’s all there – the early fear of sex and getting married, total lack of interest in boys and motherhood, first love for a female teacher, recognition of the impossibility of one’s love and desires in society as it is – which is, simultaneously, a recognition of one’s discomforting difference from other girls – proud rejection of any desire for what one believes one can’t have, retreat from feeling into the chaste world of the mind, etc. and so forth. Thousands of lesbians all over the world could see themselves in Barkova’s early life. By comparison, Tsvetaeva’s theoretical polemic on Amazons and their perfect (but infertile) unions, though rooted in the poet’s own lesbian experience, seems overly intellectualized, too artful and unsympathetic to many lesbian readers.

In the end, both Tsvetaeva and Barkova are lunar women in Rozanov’s sense because their creativity (or “genius” and “creative instincts” as they would say, respectively) is intricately connected with their same-sex desire. They both illustrate Rozanov’s belief in the “lavish fruits that people of the lunar light have brought to the table of world civilization.” The seed of Tsvetaeva’s mature creativity was sown through her submission to her love for another woman, but it was her renunciation of same-sex desire that fertilized that seed, causing it to bloom into some of the most brilliant, original and powerfully magic poetry in the Russian language. The seed of Barkova’s creativity was sown by her proud rejection of her lesbian desire, fertilized for many years by the aesthetics of her will to power. It produced ordinary creative fruits whose future yield was endangered by the thin, too caustic soil in which they were forced to grow. Only when Barkova’s plants were forcibly uprooted and transferred to a richer poetic soil where they could soak in the heat and light generated by the poet’s submission to the love she had proudly renounced did her creativity reach its maximal potential, blossoming in some of the most moving and powerful lesbian lyrics in Russian poetry.