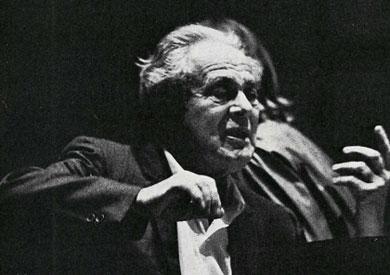

Monteux was an example of a conductor who had the natural ability to hear with his inner ear. He could not even play piano, but he had this marvelous ability to learn a score and

Burgin as the new concertmaster of the BSO, early 1920s.

hear it in his head as he learned it, so that when he came to the first rehearsal of a new piece, he knew it so well, we were all amazed at how he would notice the slightest mistake that anybody made despite his never having heard the piece performed before.

Sacre de printemps:

The first time I played Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring was when Monteux did it with the BSO in 1922 shortly after I had become concertmaster. I was simply astounded by that piece. For three weeks I walked around as if I didn’t know what had happened in the world, as if a revolution had taken place. I had the feeling that something very important had happened to me but I could not really clarify in what way. I only knew something tremendous had occurred, that life was not the same anymore. Those sounds, those rhythms, they were completely new to me; the polytonality, the general drive, everything about it, there was not one measure that didn’t stir me, and I felt completely at a loss. I couldn’t even say that I disliked or liked it, no. It was something way beyond that; it was as if something phenomenal had happened in the musical world.

We rehearsed Sacre very well and were led by a man who knew the piece inside out. That was before we belonged to the union, of course, and time was of no consequence—we had two rehearsals a day lasting 3 ½ hours each—but nobody dared to say even one word because most of us felt that that was a new way of making music. In fact, there was a feeling we could have rehearsed it even longer because everybody sensed that it was a very important thing.

It was 1922 when I first came in contact with Serge Koussevitzky on a person-to-person basis. About twelve years before that happened, when I was a student at the Petersburg Conservatory, my colleagues and I knew of Koussevitzky as a great artist on the double-bass and as a conductor of his own orchestra. We students always looked forward to the concerts which he conducted or which were given by guest conductors of his orchestra. We always looked forward to those concerts because of the excellence of the orchestra which he himself created. It was known as the Koussevitzky Orchestra and was founded in Moscow, but they gave a series of concerts in Petersburg. They always gave interesting programs and at that time, very avant-garde ones. I think I first heard works by Debussy, Stravinsky, and Scriabin at those concerts. They were always Koussevitzky’s favorite composers.

I met him in Paris when I was on vacation for the summer after my second season in Boston. Of course, I stopped in Paris and happened to be present at a concert given under Koussevitzky’s leadership of an orchestra composed of French musicians. I saw him after the concert, introduced myself, and was immediately invited to come to his house the very next day—which I did. There was something about Serge Koussevitzky; as soon as you shook hands with him you felt completely at ease; there was some charisma about him that made you feel comfortable.

I enjoyed a conversation with him lasting almost two hours in which I gave him information about musical life in the United States. He asked me to come again a couple of days later, and I did so. When I left Paris, I carried with me a wonderful feeling of having spent a few hours with a person who was warmhearted, who made you feel at ease, who was what we call a grand seigneur. He also told me that he probably would come to Paris the next summer, and that I should be sure to see him again.

In April of 1924, Mr. Monteux told me that he was leaving Boston. It was for purely personal reasons and was not yet officially announced. I expressed my sincere regrets and asked him, naturally, who his successor would be. He said he was not at liberty to tell me the name, but to rest assured because it was somebody I knew and had seen the year before. I drew the proper inferences and when I went to Paris, I just went straight to see Koussevitzky without an invitation. Again, he received me warmly and asked me more questions. I had to go into all kinds of details about the orchestra although he still did not say that he was coming as the next conductor. Only the following day did he finally break down and say, “Yes, I will be your next conductor.”

From then on, my association with him brought me in contact with him every single day, not only in our professional work, but also in his home. I almost became a member of the family and I became very attached to him as a person. I admired him for certain traits which, to me, were very important. He was a person of great integrity. He was very tolerant—with the exception of one thing. He couldn’t stand a lackadaisical attitude towards music. That really rubbed him the wrong way. Otherwise, he was very sympathetic to the problems of the musicians with whom he dealt. I admired him as an artist because of his enthusiasm, his involvement with the work he was doing.

However, unlike Monteux, but similar to many conductors, Koussevitzky lacked the natural ability to hear music with his inner ear, an ability that is necessary for studying scores. He did have the ability to listen to music when it was performed. Despite his outstanding talent, Koussevitzky’s musical experience and knowledge lay in his intuition more than in education. His greatness as a conductor came from his ability to project his natural talent despite the obvious shortcomings in his musical education.

So when Koussevitzky came to Boston, he needed quite a bit of help, musically, and he made a happy choice in employing Nicolas Slonimsky as his private assistant. Slonimsky, whom I knew very well and was in practically daily contact with at the beginning of Koussevitzky’s tenure, was an outstanding musician, in fact, unique. Slonimsky did everything for Koussevitzky that he needed, he prepared and coached Koussevitzky in every detail of the music he would conduct, from reading and analyzing the scores to playing everything for him on the piano. He also acted as Koussevitzky’s musical secretary. In a word, Slonimsky was a very important person for Koussevitzky, probably one of the reasons why Koussevitzky did not leave the BSO in discouragement after the first couple of seasons, when he and the orchestra went through a natural, but sometimes very rocky period of adjustment. Koussevitzky liked Slonimsky very much, but his second wife, Natalya Ushakova, did not, and since she also had a great influence on Koussevitzky, Slonimsky eventually left.

There is no doubt in my mind that as a team, the orchestra came to work ideally with Koussevitzky. Achieving such teamwork did take a certain amount of time, and during the period of transition when we were getting used to a conductor who differed extremely from his predecessor, all sorts of rumors arose about problems of communication between Koussevitzky and the men in the orchestra.

It is true, as has been widely noted, that sometimes Koussevitzky was hard to understand in English. Not to belabor this point because it has been already exaggerated and has little to do with true communication, I do remember an amusing linguistic miscommunication that happened between me and Koussevitzky. We were rehearsing in the Shed [at Tanglewood] when he suddenly shouted something to me that sounded like “Alt-Holn!” Puzzled, I looked up and said, “Alt-Horn? There is no Alt-Horn in the score.” “No, no, I didn’t say ‘Alt-Horn,’ I said ‘alcohol,’” said Koussevitzky impatiently, adding in Russian excitedly, “A bee just stung me on the nose.”

Aside from such unimportant things, however, the so-called problems of communication between the orchestra and Koussevitzky when he first came to Boston, were, to my mind, quite in the nature of things. They happen in every orchestra. A conductor who comes new to a first rate orchestra needs several years before he gets the orchestra to play the way he would like them to play. The important thing is that Mr. Koussevitzky overcame whatever difficulties he had initially with the orchestra, and comparatively speaking, he overcame them relatively quickly. After a couple years everybody understood and felt what he wanted.

Actually, there was a time for telling Koussevitzky almost anything, only you had to find the right time. And to find the right time, you had to see things from his point of view. For instance, if he had been preparing a new work devotedly, at that moment he himself regarded that work as a great masterpiece. If, after the last rehearsal, he asked you for your impression, he would naturally be irritated if you told him there were some things in it you didn’t like. He had to believe in the work totally if he was going to be able to give himself up to it completely at the concert. Before the concert, if he asked you about it, all he wanted from you was confirmation. A month or two afterwards, he would recognize the weak points in the composition, perhaps he would even repeat your opinion as his own. But before the performance his faith must not be shaken.

There was also talk, as the years wore on, about the rarity of guest conductors during the Koussevitzky regime. I don’t know, really, what the reason for that was. Actually, the practice of inviting guest conductors is a comparatively new procedure in the business of music. In my youth, it was a very rare thing, almost unheard of, to engage somebody to conduct somebody else’s orchestra because an orchestra and its conductor were considered one unit. So guest conductors were rare birds. But later, and especially here in America, inviting guest conductors somehow became a common practice, a practice that reflected the so-called star system and went against the original idea of the conductor and orchestra as one unit. And when you think of the BSO before Koussevitzky came, before Monteux, then the regular conductor was Karl Muck and I don’t think there were any guest conductors, then. It was naturally considered the orchestra would be at its best with the regular conductor. So, that was probably the basis of Koussevitzky’s reputed “dislike” of guest conductors.

Later, because of pressure from the audience, the board of trustees, and maybe the management, Koussevitzky was persuaded gradually to change his way of doing business. The musical justification for the practice of guest conductors is that no conductor can conduct every composition, so it is perfectly all right, once in a while, to invite another conductor who supposedly specializes in compositions which the regular conductor doesn’t like or has already done. However, having a constant change of conductors isn’t very good for an orchestra. Every conductor has his own little ideas, a great deal of time is wasted in rehearsal to adjust and re-adjust, and it creates a situation where it is no longer important what is played but who plays it. That, of course, is actually detrimental to the music. So I don’t see anything wrong in Koussevitzky’s preference for having few guest conductors.

Ultimately, Koussevitzky’s greatest asset was that he could convey his own tremendous enthusiasm about music to the audience. To him, each concert was a new experience. He was just not cynical at all. He still loved the music no matter how often he played the same work.

People have called the BSO the most perfect orchestra during Koussevitzky’s tenure and although it is very difficult for me to comment on this opinion since I was one of the participants in that “perfect orchestra,” I am very suspicious that such an opinion is really wishful thinking simply because it is not quite realistic. An orchestra changes constantly. Hardly a year goes by where out of 100 people, for one reason or other, two or three or more either leave, or die, or are sick. Boston was a little bit more fortunate in this sense, because the turnover was smaller than anywhere else. At one time that may have been because it was not a union orchestra, but later on, we were unionized and the turnover rate was not affected.

Koussevitzky was with the BSO for twenty-five years. That’s a long period, a whole generation, and naturally, when he got used to all the players and when the players got used to him, a family feeling developed, and no one discharged someone just because he disliked his appearance.

Koussevitzky also had one thing that I think is especially important for conductors to have—a great deal of imagination and a convincing way of making music and enjoying it. That rubs off on the players no matter how cynical they are. Sooner or later they fall for it. Koussevitzky was sometimes wrong but when he was right he was sublime.

With Koussevitzky there was very little cynicism among the orchestra members and there were reasons for that. Having been originally a bass player himself, and being very independent due to his financial situation, he really tried to take care of the members of the orchestra. He took a personal interest in everybody’s well-being. And whenever there were gripes with the management, one could always count on him being on the side of the orchestra. So naturally, the players could only reciprocate this attitude with a sincere desire to please him.

There is one thing that people are apt to overlook when they speak about orchestras, even conductors sometimes don’t realize it, and that is that musicians in the orchestra do not perform for the audience. A soloist, when he stands up in front of the auditorium, performs for the audience, but the musicians in the orchestra perform only for the conductor. It couldn’t be otherwise because when you have four horns, let’s say, and you are playing a Brahms symphony (where Brahms actually uses only two horns except we had four in the BSO), nobody in the audience can say whether it is the first horn that plays something, or the third horn who plays the same subject in a different tonality. Neither could anybody say whether it’s the first oboe or the second. People assume that if it’s a longer melody, it’s probably played by the first-desk player, but the listeners don’t see who is playing what. The player, however, is very eager, whether he’s second, third or first chair, to play for the conductor so that the conductor gets affected. The conductor is his listener.

Now, when a conductor is aware of the player and when he indicates, maybe just by a twinkle in his eye, that he is aware that he’s playing and is pleased, the player thinks, “That is the man I am playing for,” and he plays his heart out for him. On the other hand, if the conductor doesn’t notice, or is not quite aware that the individual player is there, or doesn’t look at him, or if he’s doing something else, then such a conductor is no conductor to him. A player, a performer, needs an audience, that’s what makes a performer. So, Koussevitzky had this awareness of each individual’s playing. When he heard somebody play and it appealed to him, he could almost be brought to tears and for a performer that is very, very inspirational. There are great conductors whose faces are completely immobile; they are very well aware of who is playing but they take it all for granted. And they are right; they should take it for granted, on the professional level. Psychologically, however, even professionals who understand that they are expected to play well, still want to be appreciated. And although Koussevitzky could get very angry at individuals in rehearsal, he could also show real appreciation for individual performances. That’s part of the reason why I would say that the give and take between the orchestra and the conductor during Koussevitzky’s tenure was the best that could be desired.

Koussevitzky was deeply affected by music. He became part of the composition he had to conduct or perform. He absorbed the composition, and perhaps the composition absorbed him. Therefore, he probably felt towards the composition just like he felt towards the orchestra. He identified himself with the orchestra and called it “my orchestra.” It was not the Boston Symphony Orchestra, it was his orchestra. I think that he felt that way about music he performed, too. So whether he performed the Pathetique or the Romantic, the Ninth by Mahler or the Ninth by Beethoven, it was his piece. I think that was one of his strong points and because he carried a great conviction about the performance, he communicated that to the audience.

I might mention an anecdote at this juncture. After Koussevitzky performed a particular work of a contemporary European composer, the composer’s compatriots surrounded him and asked him how he liked it. He said, “Well maybe it wasn’t exactly what I intended, but it was good. It was very good.” I think that says a lot. If it’s very good, it really doesn’t matter if it’s a little different. Perhaps, it should be a little different; otherwise, life would be too monotonous.

[As Robert Sabin noted in Musical America (March 1962) on the occasion of Burgin’s retirement as concertmaster: “The world-renowned refinement and intellectual distinction of the Boston Symphony owe much to Mr. Burgin’s leadership. […] Everyone knows of Mr. Burgin’s brilliant career as a concertmaster, but many people are not equally aware of his distinguished achievements as a conductor.”

In 1924, when Serge Koussevitzky contracted a severe cold just before a performance of a new work, Honegger’s Pacific 231, Burgin stepped in to conduct the BSO for the first time. From then till 1934, he became the regular conductor of the Boston Symphony’s Young People’s Concerts and was a Guest Conductor of the orchestra on an annual basis. When he already had some say in making his own programs, he revealed two noteworthy aspects of his work as a conductor, in general: his personal fondness for the music of Bruckner and Mahler which informed his pioneer efforts to perform their works, decades before they became the staples of orchestra programming they are today; and his profound interest in and enduring commitment to performing contemporary and “new” or undeservedly forgotten music.

Withal, he conducted seven world premieres with the Boston Symphony, works by Toch, Harris, Dukelsky, Menotti, Cowell, Blackwood and Moevs. Burgin also introduced to the United States works by Malipiero, Shaporin, Poot, Krenek, Langendoen and Foss. His numerous Boston and Tanglewood premieres included four works by Hindemith—he also gave the US premiere of the Hindemith Violin Concerto in April 1940—as well as works by Miaskovsky, Krenek, Vogel, Levant, Lopatnikoff, Mahler, Creston, Revueltas, Haieff, Vaughan Williams, Shostakovitch (the Fifth Symphony which he introduced to Boston in 1939 after Koussevitzky rejected it), Khatchaturian, Ives and others.]

My role in the BSO as assistant and associate conductor to Koussevitzky was sometimes complicated. Part of the issue was inherent in the position itself.

Burgin conducting the BSO with soloist Samuel Mayes, 1958.

First of all, an assistant or associate conductor is simply a necessity in every major orchestra to fill in for the main conductor at short notice because of scheduling conflicts, sickness, or something like that. One cannot get a guest conductor on five hours notice or sometimes, as happened to me, five minutes notice. Once, when I was already on stage to begin the concert as concertmaster, I remember being called back to the green room and told to put my violin away and conduct since the conductor had suddenly taken ill and couldn’t do it. That is the position of an associate conductor. Every conductor in other orchestras also had an associate conductor and Koussevitzky, as a matter of fact, suggested that relatively late. He originally intended to conduct all the concerts, but when he found that that was physically a little too taxing, he considered having an assistant conductor and he chose me.

As associate conductor with Koussevitzky and Munch even when it came to my own programs, I was obviously limited in the selection of works I could conduct since my programs had to fit in, first of all, with their programs and like every associate conductor, I had to get the main conductor’s permission, even in the case of works which he didn’t have plans to do.[2] For a complete list of Burgin’s programs with the BSO, see Appendix 2. So, there were always certain problems involved in making programs. There were also occasionally issues involving personalities, vanities, rivalries, that sort of thing.

I remember, for example, one episode that happened after George Szell had come as a guest conductor [January 1945]. Just before he left, I was informed suddenly that I would be conducting in Boston after Szell’s departure. Koussevitzky had decided to make himself absent for three weeks. I thought at the time, maybe he believed the transition from Szell to his appearance would be softened if I conducted in between.

Another example of the complexities of being an associate conductor concerned Koussevitzky’s attitude to Soviet music. On one hand, he was always very interested in contemporary music and in new Soviet composers. It took years, however, before he himself would establish musical relations with the Soviet Union. The first time the BSO played a work by a Soviet composer was during the 1928-29 season when I conducted Miaskovsky’s Eighth Symphony. Almost ten years later, things hadn’t really changed. Koussevitzky at first announced his intention to conduct Shaporin’s Symphony in the 1936-37 season, but then he changed his mind, cancelled it, and gave it to me to introduce to Boston in 1938-39. When asked why he had decided not to conduct it, he claimed there was no political significance in his decision; he simply had not had time to study the score. Actually, he had expressed a liking for Shaporin’s work. Yet, I don’t know if his not having enough time was the whole reason. And maybe politics wasn’t either. At first, he did not want to conduct the Shostakovich Fifth with the BSO, and so I was the first one to conduct it in Boston (in the 1938-39 season). But when Koussevitzky heard me conduct it, and heard the success it had with the audience, that was the end of it for any program of mine, I couldn’t touch it anymore until after he retired.

When Koussevitzky was invited to conduct the Shostakovich Fifth with the New York Philharmonic, I happened to be sitting at that concert next to Otto Klemperer who was hearing it for the first time. Klemperer and I were well-acquainted, we had met in Germany, and when he saw me at the concert he remembered me right away. So we sat together and Klemperer listened very intently. His first words about the piece were: “Aber das ist ja Mahler, Gustav Mahler.” (But that’s Mahler, Gustav Mahler!) And he was right.

Burgin rehearsing the chorus for Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, 1962.

It is true that Shostakovitch was very influenced by Mahler whom he got to know through Solovetinsky, a music critic, reviewer, and writer about music who knew Mahler’s music very well and was a close friend of Shostakovitch’s and had a great influence on him.

Speaking of Mahler, it was difficult at first for me to program his music when I conducted the orchestra. I wanted to do the complete Mahler Fourth, but the trustees said no. Mahler (in the early 1940s) was taboo—people considered him long, tedious, and everything else bad. I always liked Mahler very much; so I compromised and asked to do the last two movements of the Fourth. They agreed. Then, after the performance, we got letters asking, why don’t we do the whole symphony? So I was allowed to do it later that season. Things had improved greatly in the fifties and sixties—my Mahler programs with the BSO generally had an enthusiastic response from the orchestra and the audience.

The BSO is very proud of Tanglewood and they should be. Of course, Koussevitzsky played a very, very important role—he was the initiator of the idea and the guiding spirit behind its creation. But I was the one who persuaded Koussevitzky how the Academy, as they called it then, should be set up.

That happened in August 1939 when a meeting was called at Tanglewood with Koussevitzky, Judd (the manager), and anyone else who wanted to participate, to discuss the proposed Academy. Before leaving for the meeting, I jotted down an outline of my ideas for the instructional program and I intended to read it at the meeting. However, at that first meeting, which lasted over two hours, nothing was accomplished. Everybody was talking and nobody was listening. I realized that if this was the kind of meetings we were going to have then nothing would get done.

After supper that evening, I took Koussevitzky aside, made him listen to my plan carefully and asked him to make possible suggestions point by point. I explained every sentence, as if I had to read it to a child. Finally he understood everything and agreed that nothing should be changed in regard to the plan for the Academy. And that’s how it was first set up.

The BMC has evolved over time and now (1970s) they have changed the orchestral program that I directed for many years. Some of the works which I originally suggested as a must for study began to get slightly obsolete although they are still played. Anyway, what I stressed when I was in charge of the BMC orchestra, was the importance for each instrumentalist who participated,—because they were students, not professionals,—to have an opportunity actually to perform what professionals considered the difficult part for their instrument of a major work in the repertoire. And I didn’t decide on works for the BMC orchestra to perform by using only my own judgment, I asked every instrumentalist in the BSO for their opinions. And I found that they came up with some amazing answers, which I would never have thought of.

For example, I asked a very dear colleague of mine, a horn player, if he could tell me what he considered a particularly difficult part for horn in the orchestral and opera repertoire. I would have thought that he would mention some Strauss piece like Don Juan or Till Eulenspiegel. But he said, “From the point of view of the difficulty of performing a few measures perfect, on the stage, it would have to be the second (slow) movement of Beethoven’s Second Symphony.” I was taken aback since there are very few notes to play there. I said, “Well, what actually is so difficult in that?” He said, “You don’t realize what the horn player goes through when he sits there for about seven minutes, not playing, and then has to pick up his horn and start on a high B…”

I have always looked upon a composer as a kind of enigma. How does it come about that he creates this piece of music? This question arose in my mind especially when I was in close contact with a composer as was often the case when I was conducting his work or when I played under his direction. And it wasn’t only the composition that interested me, but the composer’s personality, his whole attitude and how he went about communicating, outside of his music, with the musicians whom he needed in order to have his work performed. And in this respect, three great composers made a particularly great impression on me, actually there were four, but the fourth one did not conduct the BSO, so my contact with him was not close: Bartok, Schoenberg, Hindemith and Stravinsky. Bartok was only present at our performance in Boston under Koussevitzky of his Concerto for Orchestra which was commissioned by Koussevitzky for the 50th Anniversary of the BSO. It’s a great work and the BSO should be proud that they were the ones who brought it about.

Schoenberg was an unforgettable case in many ways. First of all, I was awe-stricken by the man and also by his work, which was something new. It was something that I worked very hard to understand, it was a new idiom, a new world. Hindemith was the closest of all to me and we became good friends. I had several encounters with Stravinsky because he conducted several times and I also had the great privilege of playing under his direction, L’Histoire du Soldat.

It is well known of course that Schoenberg had to leave Germany when the Nazis came to power. In fact, he was lucky to have been able to escape. And everybody I knew in the musical world in the United States felt an obligation to invite him to conduct their orchestra, as did Koussevitzky. That was the least they felt they could do because they themselves did not do anything to perform his work, or very little, except for “Transfigured Night.” Koussevitzky was aware that Schoenberg was a personality, that he had done something important in music. Perhaps we did not quite understand what his innovation was but we felt instinctively that something had happened. So Schoenberg was invited to come and conduct the BSO. I was somewhat familiar with Schoenberg though at that time I will admit he was an enigma. Still, I felt that he was also something that only happens once in a lifetime.

I myself had already conducted his Pierrot Lunaire.[3] Concert of Modern Music under the auspices of The Chamber Music Club and of the Flute Players’ Club, Jordan Hall, Monday, April 23rd 1928. The program also included the Stravinsky Octet and Hindemith’s Six Songs from Das Marienleben and Gruenberg, The Daniel Jazz. That was in 1928 in Boston. There was an organization of rather snobbish members of the Boston elite who supported private performances of interesting, worthwhile new works and chamber music. And I talked them into sponsoring a concert for Pierrot Lunaire. I also convinced them it was a piece that was not suitable for playing in a room and it would also be nice to give a wider audience of listeners a chance to hear it. They agreed, and supported the concert financially. We rehearsed that every day for three weeks. But that was several years before Schoenberg came to conduct the BSO.

When Schoenberg came, from the very first rehearsal, there was something about his personality, at least to me, that put one in awe of him. I looked upon him as if he were a person who had come from another world. And when he conducted, he conducted not like a professional conductor but like a composer conducts his own work. Every remark he made was so to the point and nothing was unnecessary, no stories, no affectations, nothing but purely technical remarks about the music. However, his selection of works for his program was a disappointment to me—they were: an arrangement of a Bach piece for organ, Verklärte Nacht, and Opus 5, Pelleas und Melisande. Still the old type of music but when he did that, his remarks were very interesting. I had no opportunity to speak to him during the rehearsals, I just watched him, took in everything he said. Everything went pretty well, we had our regular four rehearsals and then came the concert.

That first of his concerts took place in Cambridge, in Sanders Theater. We were already warming up when I was told Schoenberg would like to speak with me. I thought that he probably wanted to make some last-minute comments for me to tell my colleagues, to remind them of certain things. I took my violin and went downstairs to the conductor’s room. And I started to speak—the conversation was in German—“Is there something you would like me to say?” “No, no,” he cut me off, “It has nothing to do with today’s program at all. I just heard that you did my Pierrot Lunaire some time ago.” “Yes, I did,” I replied. “Well, did you find it a difficult piece to put together?” “Yes,” I said, “as you know, it is a difficult piece. And it was new to us.” “Well, how many rehearsals did you have?” “We had seventeen with the players alone and then we had five more with the singer—we got her from New York.” “Well,” he said, “that is very nice to hear. But I hope you did not perform that in Symphony Hall?” “No, no, we didn’t.” “Where did you perform it?” he asked, and I replied, “In the hall of the New England Conservatory, Jordan Hall.” “And how large a hall is that?” he asked. I said, “It has a capacity of 1200 seats.” “Oh,” he sounded disappointed, “that was much too big a hall.” And then I made a repartee which I consider to be one of the most stupid of the century, so to speak, probably because I was in such awe of him. I said, “Maestro, es war nur halb voll, it was only half full!” Which in fact was the case.

It was the most idiotic thing to say but he was such a wonderful person, he simply ignored my gaffe and fell in with my unintentional witticism, saying, “Thank goodness!” That immediately put me at ease. So I said, “Maestro, why are you so happy that the hall was only half full?” He then became quite serious: “I’ll tell you, and I’m speaking from my own experience. You know, I understand that Boston is considered one of the really musical cities in this country and I have no doubt it is so. But I do doubt that you could find more than 600 people in this city who would enjoy and be interested in listening to a work like Pierrot Lunaire. I say that from my own experience. Therefore, if you had more than that, or if you had a full house, you would have 600 people who would hate this piece. And let me tell you, there’s nothing more terrible than to sit next to a person who hates the piece that you’re interested in. I myself have been present at concerts of my work where people next to me hated my music, and we almost got into a fight!” Which was actually true.

I realized quickly that what he was really trying to say was that Pierrot Lunaire is a chamber piece and is not ideally suited to a large hall. But his attempt to put me at my ease with his wonderful wit and self-irony was so typical of him. Then, I had the courage to say, “You know, Maestro, allow me to tell you that I was a little bit disappointed that you didn’t select for your program a more recent composition than ones you wrote at the time you wrote Verklärte Nacht.” And he said, “Well, I don’t see why I should carry on my shoulders the responsibility of atoning for all the sins conductors have committed by not playing my music. Just because you people don’t play my recent works, why should I be the one to bore my audience with them?” Schoenberg was really a unique person.

Hindemith was, quite simply, a great personality. There was hardly anything in music about which he lacked the authority to say something worthwhile. He also believed that it was not worth arguing with someone unless he could answer your question, that is unless he could explain “Why?” rather than simply make a statement about what he thought.

Hindemith and I were very often together in musical endeavors. I played under him, conducted his works, and also played his violin concerto in this country for the first time. I gave the first performance in April 1940 and later Ruth took it over and played it all over the United States.

How I ended up giving the first American performance of the Hindemith Violin Concerto came about in a very strange and roundabout way. When Hindemith came to this country, I think it was in 1938 or 1939, and I got to know him, we became very friendly. On the whole, he was not a very easy man to get to know, but he took a liking to me, and I was very happy about it. And we used to argue about many of his works. I played his quartets, the first and second, and I also liked his Kammermusik No. 4, which I found terribly difficult and still think is a difficult thing. In fact, I could never manage to play it well enough to my satisfaction although I studied it hard. And the only satisfaction I had was to have a pupil who managed to play it very well, and I enjoyed it very much when he played it for me.

Anyway, when I got to know Hindemith a little better, I once said to him, “Paul, I have been practicing your Kammermusik No. 4.” “Why do you waste your time studying that piece?” he said, which was very strange to me. “It’s not worth the time you are spending,” he continued. And I said, “I can’t understand why you say that. I like it, but I don’t understand why you write so difficultly for the violin because you’re a violist and a violinist.” He repeated, “As I said, I don’t see why you bother with it.” And we got into an argument, but you can’t argue with a composer who evaluates his piece not according to your ideas. However, I finally found something that stopped him. I said, “You know, Paul, the moment you compose a piece, and the moment it is printed, you lose all jurisdiction because anyone can take it and has the right to express his opinion.” Well, that had an effect. He said, “Well, that is true,” and there was no more argument. Then he said, “You know, I am going to send you a concerto for violin and orchestra,” and added, “wenige Noten aber schön.” (“Fewer notes, but beautiful.”)

And that’s how we left it. Shortly afterwards, I performed his piano quartet with clarinet, violin and ‘cello in E flat—I don’t know why people don’t play it. It’s a beautiful work. That came about because the Schott people, his publisher, were trying to promote him in this country. They arranged concerts of his works and wanted to arrange a New York concert. They had already engaged people, but he said, “No, I want to have my friends from Boston come and play it.” So Sanroma, the pianist, Polochek, a BSO clarinetist, and I had to prepare the work despite the fact that there were plenty of musicians in New York to play it. But he insisted that he wanted us, and so we did it.

Finally, he had to go back to Germany—he had come here alone, without his wife—probably to settle his affairs because ultimately, he knew he would come to the US if he could. He was not very friendly with the Nazis and they were not very friendly to him. And, his wife was Jewish. So, about two weeks before he was due to leave, I still hadn’t heard anything about the new concerto which was supposed to be so beautiful, and with fewer notes—that was very important! For a while I thought that it was one of those nice things that a composer promises you but forgets about and there was nothing to be done. But then, I thought, “Why does he bother to send it to me? He’s published, after all.”

And when I went to say good-bye, I said, “Paul, about that concerto you told me you would send me, why do you bother? I can buy it, your publisher is Schott, right?” He said, “Of course, Schott is my publisher.” He said, “But you can’t buy it yet.” “Why?” I asked. He replied, “Because it’s not yet in print.” Then I said, “Listen, could you let me see a manuscript of it, something,” because I was so eager. I had loved his music before I even knew him. “Well,” he said, “I’m sorry, I haven’t got a manuscript because it isn’t written down.” I thought he was pulling my leg because he had already told me that I could not have the first performance because he had already promised it to a certain violinist and the premier was set for September 19 [1939] in Holland.

So I said, “How is that possible? It is now May and you tell me it hasn’t been printed, it hasn’t been composed, there’s no manuscript, and yet it’s going to be performed on September 19th?!” He said, “I didn’t say it’s not composed. It is composed, just not written down. I’ve got it all composed in my head but I haven’t written it down yet.” Well, such things were new to me. I could not disassociate composing something from writing it down. I still thought that was the same thing. He continued, “Well, you know I’m taking the boat to Europe and I’ll be on the boat six days. There’s nothing else to do then so I’ll write it down, and when it’s written down my proofreader will check the manuscript, okay it, and then it will be printed and performed.”

Hindemith was in fact very akin, in his manner of composing, to Bach or Mozart. As we all know, Mozart could write out an opera overture the night before the performance, it was all already composed in his head. He didn’t have to change anything. Or Bach was able to dictate the Art of the Fugue from memory because he himself did not write it down, also as everyone knows.

Burgin and the BSO applauding Posselt after her performance of the Hindemith Concerto, Leonard Bernstein conducting (Tanglewood, July 1947).

Hindemith was a unique case and I valued my experience with him highly because I was always so interested in how composers do things, compose and create. As a matter of fact, he finished writing down the last two or three pages of his E-Flat Major Symphony in my house in Jamaica Plain, very early one morning, around 5 A.M.

I finally got the violin concerto, but only in February 1940 and only after writing to the Schott representative in London and pestering them. They at first replied that they had not gotten it yet. At last, they sent me a facsimile of the violin part with a letter asking me to inform them immediately when I would perform it because they had a great demand for the concerto and Mr. Hindemith wouldn’t allow anybody to have it until I had performed it. And that really made me mad. They sent me one copy of the violin part and expected me to know the concerto without anything else. I wrote back that I could tell them nothing until I received the score both for my self and for the conductor.

Well, finally in February the music arrived and I did perform the Hindemith with the BSO and Koussevitzky, in April, and about a month later I had to have an operation. While I was recuperating, my wife learned the concerto and played it so beautifully that she eventually played it with Hindemith in New Haven, in New York and everywhere, all over the country. It really is a beautiful work, beautiful. And with fewer notes.

I later realized that Mathis der Maler was a turning point in Hindemith’s work and ushered in a new period in his compositions and attitude to music that perhaps he did not want to acknowledge. The only exception might be something he recommended to me, a work which I love very much, The Four Temperaments, a suite for string orchestra and piano—a beautiful piece. I don’t know the year it was composed but I think it was written just around the time of Mathis der Maler. Hindemith also told me that there were some nice things in the third quartet, but everything else he wrote before Mathis, you couldn’t even mention to him. His remark about the violin concerto, “Wenige Noten aber schön,” was also very apt. There were too many notes in all his earlier work, but like most composers he gradually got rid of those superfluous barnacles that seem to attach themselves to the main body.

As a conductor, Stravinsky was very insecure. It was a psychological issue with him. He told me when he went on the podium, he had a fear that he would fall down—he had this feeling of falling. He told me that after he conducted his new work, Jeu de cartes, with the BSO (Jan, 1944).

Photograph of Igor Stravinsky inscribed to Burgin, 1940.

He was marvelous in rehearsals—every word he said was meaningful, nothing was wasted. But in the performance, he simply got lost in his own piece. That is, he made a little technical mistake due to the large number of irregular, asymmetrical measures in the score. That kind of mistake does not faze an experienced orchestra of players whose parts have them playing continuously, without rests. When they notice that the conductor has made a mistake, they keep on playing and the conductor will find his place. But, the players of instruments like the winds in that piece who do not play continuously and have measures to count and cannot watch the conductor all the time during the rests but look for either a cue, or know approximately when to come in and then look at the conductor, they can get confused.

In this performance, when Stravinsky forgot where he was, we violins and cellos just stopped watching him and played on. Our rests were only one or two quarter notes, which didn’t keep us from staying in time. But the wind instruments had rests for ten or twelve measures at a stretch and those measures were in all different rhythms. When they finally thought they had to come in, they looked up for their cue, but the beat was not directed at them. Besides, Stravinsky himself was already nervous, wondering where he had made the mistake and turning the pages of the score back and forth. It was a real calamity.

Now, in Jeu de Cartes, the movements are called “hands” (deals); there are four of them, and each hand starts in the same way. What had happened was that before the first hand was finished, someone started the second only to hear his neighbor whisper, “No, wait, it’s not time yet.” Several attempts were made to right the situation. In the meantime, Stravinsky was completely at a loss. He heard something was not right and tried to find the place where he thought we were, but we were nowhere. There was nothing to be done but stop playing altogether, and for a moment, we stopped. Then we started a new movement, and it was all right.

But I have never seen a person in such a despondent mood as Stravinsky was after this performance. He asked me to come and talk; he felt more at ease with me because he could speak Russian—not that he couldn’t speak other languages, but he felt more at home in Russian. He called me upstairs and began, “Tell me, Richard Moiseyevich, what happened?” Well, I could not tell him straight out that he had made a mistake, so I said the next best thing, “Evidently there was a misunderstanding between the orchestra and you.” “No,” he replied, “it goes deeper than that. Do you realize this is the same as a situation where Igor Stravinsky has forgotten his own name? It’s amnesia. Imagine, Igor Stravinsky, I mean, the Igor Stravinsky suddenly doesn’t even know his own name. It’s not like making a mistake conducting another composer, it’s a mistake with your self.” It was very difficult to calm him down. “Yes,” he said finally, “I know what it is. When I go up on that podium, I get frightened, scared, as if I am going to fall down.” It was a typical Russian situation out of Dostoevsky!

[Burgin worked with Munch for thirteen years, roughly his last decade as concertmaster of the BSO. He wanted to retire two years earlier than he did, but Munch persuaded him to stay on until his own retirement. Despite a personal liking for the Frenchman, in private Burgin was critical of Munch’s unpredictableness as a conductor and the “lack of balance in the extreme” that sometimes characterized Munch performances.

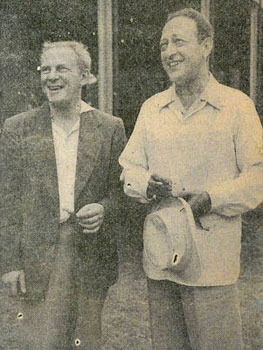

The following impressions and anecdotes about Munch and his conducting come from Burgin’s private correspondence with his wife. They refer to specific incidents and performances that took place during the BSO’s transcontinental tour in April–May 1953.]

I liked Munch at the beginning, and often think that certain things he does, like giving five hundred dollars for [violinist] Harry Dubbs [after he suffered a serious, ultimately fatal heart attack], and many other things are in themselves admirable. Still, his gestures of generosity are sometimes so out of proportion, so distorted, as his music making is at times, that I can not help feeling, such a person could easily go to the other extreme, and become mean and hurtful especially if he felt insecure.

Munch in these concerts [New Orleans, 28 April 1953] is right in his element, yells, jumps and makes grimaces as if he's going to lose his mind and to hell with the music. It’s quite a show for the gallery. But what goes on with the music is simply disgusting.

Yesterday [1 May 1953] a very interesting incident happened. Munch came into the club car where a few of us were gathered just before going to bed. At the concert he had been mad as a hornet. The concert went off poorly. Nobody knew what got into him. When he came into the car, he saw me, sat down opposite me and asked how I felt. Naturally, I asked him how he felt, to which he answered, “When I do not conduct I always feel well but when I do, then it depends whether the concert is played well—if so, then I am happy, otherwise I am not, and tonight I was not happy.” “Well,” I said, “are you sometimes happy?” There was a long pause—“Yes,” he said, “sometimes.”—“In that case,” I said, “at least there is something to go by.” Everybody around had a laugh. Then suddenly, he turned to me and said, “You are the associate conductor but more conductor than associate.” I asked, “What does that mean?” No answer. Suddenly, he invited everybody to have a drink. Scotch and soda. Another one, and so on. He got in a better mood; the conversation was rather pleasant, everybody participated. Suddenly he turned to me and asked, “Tell me, what do you do to obtain the Koussevitzky sonority from the orchestra?” I looked at him with a blank expression and asked: “What do you mean by that?”—“Well,” he said, “How do you succeed in getting the Koussevitzky sonority?” I looked around at everybody and had a feeling that they all knew what he was talking about, but I hadn’t any idea. I answered, “Sonority is an expression I never use when I conduct the orchestra. I confine myself to purely technical terms and don’t know what Koussevitzky Sonority means.” “Well,” he said, “That is what W. S. Smith wrote after the concert you conducted.” And that was what had been eating him.

Last night [5 May 1953] we played before a capacity audience, an attendance of over 6000 people. The concert started off with Munch calling me into his room before going on the stage to tell me that I should not be surprised if he conducted like an old rag. He was obviously nervous and said it to get some sympathy. He added that he had not wanted to conduct tonight’s concert and agreed to do it only because Judd [the manager] insisted. Of course, he got all my sympathy and I reassured him everything would be all right. Well, he started off conducting in such an indecisive manner, that after the ninth measure of Barber’s Overture, the second violins did not know where they were.

Munch and Burgin at their retirement party after the summer season in Tanglewood, 1962.

The thing threatened to fall apart. However, the orchestra knows that piece so well that somehow we held together. Then, Munch pulled himself together and went to the other extreme. With each successive piece he got more into his element, became more and more wild, gesticulating, jumping, and yelling. Each crescendo was reinforced by a violent accelerando—the pp was inaudible. In ff the trumpets blasted away and the percussion had a wonderful time. In short, it was a real show. The people went wild.—The success unprecedented, the musicians bewildered. In sum, a real Munch performance. We played a couple of loud encores. And that brought the house down.

Munch called me to his room, just a few minutes before the concert was supposed to begin [15 May 1953]. I found Stagliano [James Stagliano, first horn] in his room. When I asked him whether he wanted to see me, he said he did and continued: “As I just said to Stagliano I wanted to tell you that I have been informed the local critic, Cassidy, is out to kill me; I am somewhat nervous tonight.” “Well,” I said, “Do you think that the attitude of a stupid critic can affect our playing tonight? Don’t worry, this orchestra can play well, and therefore you can be at ease.”

When we went out, Stagliano turned to me and said, “What a crazy fellow he is, to call me in and ask me to play well. That’s one way to make a fellow nervous. This man doesn’t know what it takes to perform in public on an instrument. A rank amateur.”

Well, we played well. He had a great success, in spite of the fact that in the second part of the program, when he felt that the audience was with him, he threw all restraint to the devil and became musically so unbalanced that we probably gave the most distorted performance of the Brahms 1st Symphony I ever witnessed.

After all, the conductor is an element in musical performance that is basically unmusical, in the sense that he is the only person that does not produce sound or create sound but nevertheless is needed to get some sound out of an orchestra.

One finds a certain timidity in composer-conductors. Many composers feel awkward on the podium. They can be very objective during rehearsals and know exactly what they want, but in concert they become too personally involved. Ravel was the classic example. He once managed to conduct La Valse in four—all the way through. Richard Strauss, on the other hand, was really first-rate—when he was interested. When he conducted in Stockholm (1917), he did some Mozart and Wagner, but mostly he did his own works. He loved Till Eulenspiegel and the Sinfonia Domestica but other than those, he just beat time. Schoenberg would pester the players in his orchestra a great deal, but he was an extremely interesting conductor; each gesture had a point to it. Prokofiev was quite good, particularly with his own works. Stravinsky was wonderful in rehearsal; he could tell you precisely what he wanted, but in a concert anything could happen.

Some conductors have very good memories, and Erich Leinsdorf was one of them. The most remarkable memory I ever encountered was that of Guido Cantelli. He knew literally every part. But even such people are not entirely infallible. Toscanini, you know, once had a memory slip and had to stop and go back to the beginning. I remember that even Monteux, whose memory was second to none, got completely lost, once. The concert was with the BSO in Paris, in 1952 I think. In a certain section of the William Schuman Symphony, the entire brass section entered a whole measure too late, and continued to play until the end of the section ahead of the rest of us, with Monteux merrily conducting as if nothing happened. I strongly suspect he was not aware of it. He conducted from memory. Igor Markevitch, who also had an excellent memory, said once that he believed that it would be impossible to write one page from memory exactly as it appears in the score. And furthermore, the same would probably be true for the composer if he were asked to do it a few weeks after it was written. I prefer to have the score in front of me. For me, it’s basically a matter of feeling secure but I also can’t forget that in my youth, playing or conducting by memory was considered an affectation, and not in good taste.

I once asked Henri Temianka which he found easier, playing the violin or conducting. He said, “Let me think a minute.” “No you don’t have to think,” I answered. “I’ll make it easy for you. Right now it is six in the evening. If I were to ask you to conduct the accompaniment to the Beethoven violin concerto tonight, would you accept?” “Of course,” he said without a moment’s hesitation. “Now,” I insisted, “if I were to ask you to play the violin concerto tonight, would you accept?” “Of course not,” he said indignantly. “Well, there is your answer.” I said.

I know many virtuosos and I do not envy them. They tell me what it’s like to play the same few pieces over and over and know they have to go here and then be there. Not for me. I like the orchestra.

Violinists and other soloists are not themselves wholly responsible for their success—it does not depend on their playing alone. They need managers and managers generally do not accept two stars, or two possible stars. Each manager ideally wants one star as well as other, lesser known artists; they sell their artists in packages and they are not going to compete with themselves. So, no matter who comes to him, if the manager already has his star, he is satisfied with that one.

There are other elements that enter into career success; first of all, age. Somehow a child prodigy affects the audience much more than an older serious musician no matter what the child plays. We cannot help that. We are amazed at the ability. When a child performs, the audience does not really listen to the piece of music the child performs, it listens to the way the piece is projected by a very young person. Actually, that is the only way people do listen to performances—though I don’t say there aren’t exceptions. Only, when a performer has reached a certain age, when he is an adult, listeners will take into consideration other aspects, not only technical mastery—that would be taken for granted—but also the ability to present a piece of music that satisfies them, rightly or wrongly. And so they begin listening to the playing itself.

I was very, very impressed with Menuhin and I remember distinctly how he played the first time I heard him. He played the Beethoven Concerto and he was only about 16 or 17 years old, which is a very young age for a violinist to play such a serious and big work. I also had some reservations about his playing, but since Mr. Menuhin is still [in 1974] a great artist, I don’t think it’s proper for me to dwell on my reservations. I may have been quite wrong.

Some people have compared Toscha Seidel with Heifetz who studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory around the same time. Toscha was there at the same time as I and was a year older. But Toscha was not of the same musical caliber as Heifetz even though he may have impressed audiences very much—he was very out-going in his manners and in his playing. Even while he was still a student, however, most of the older students who looked at things more deeply, and more professionally, did not quite believe that he would last that long as a virtuoso or even develop beyond what he had already achieved.

One of the problems with edited versions of works for the violin, is that there is no definitive type of fingering that can be considered better or worse than another; neither is there a definitive type of bowing. In a broader sense, editing a piece of music could be considered a certain kind of crime. When you edit something that a composer has written, you are actually saying not only that the composer didn’t make clear in his music how he wants his piece to be played, but also that you do know what he wants. There might be some value in editing if the editor has been in personal contact with the composer, but in most cases, he is not. Nevertheless, I always told my students if a piece is edited by somebody, they should take this into consideration and should have a certain amount of respect for whoever has edited it. Because, we must assume that the fellow who edited it was hired by the publisher and probably paid for it and therefore, we must assume that the editor had a reputation worth paying for. To say, a priori, a certain edition is no good is wrong. One should see what the editor says but keep in mind that is not always what the composer wrote. A good editor should distinguish what the composer indicated (or might have indicated) and what he is indicating. The editor may think he has improved it, but it also is possible that he didn’t improve it. There’s also the question of ability—the editor’s and the player’s. Maybe the editor isn’t quite as good as the player, and maybe, on the contrary, he is much better, and his way of doing things is not within the player’s capacity.

I once had a conversation with my good friend Joseph Gingold who edited quite a number of pieces. I asked him, “Joe, you have edited so many things and of course, I’ve seen most of them, so tell me, does the publisher tell you what type of player you are editing for, and does he provide you with any guidelines?” “Well,” he said, “as a rule they leave me pretty much alone, but sometimes, they do give some general guidance.” “What kind of guidance?” “Well, if it is a piece they want to sell and they know it is rather difficult, they may suggest that if there is any possibility of simplifying it somewhat, then to include simpler alternatives. They don’t force me to do anything unmusical, but I do occasionally have to take into consideration that maybe my edition will be used by a young student who is not quite capable of overcoming certain problems and difficulties and who doesn’t know yet that he has the right to change things for himself, as we all do, and so for such players I give simpler alternatives.” In other words, editors, even if they are excellent and experienced musicians, can not always rely wholly on their own judgment, they sometimes have to give in to the commercial aspect of editing. Therefore, I am very enthusiastic about the publication nowadays of unedited Ur-texts.

In my few contacts with composers, I’ve been amazed how lenient they are. If you grasp the essence of what they want, they will allow you to do almost anything and the last thing they’re concerned with is what fingering or bowing you use. Once you start playing, they feel you understand what it’s all about. So I think it behooves us to develop a certain arrogance, if you wish, and have a little more faith in our convictions about our understanding of a work of art before we attempt to project it with our instrument because otherwise, we can only imitate and that will be a cliché, it won’t be the real thing, no matter how well we imitate.

[Burgin’s remarks on teaching, for the most part spoken to Professor Dann in 1974 when Burgin was 81, were based on the accumulated experience and wisdom of teaching, both violin and conducting, for over fifty years. Burgin himself could not say when, exactly, he began teaching.

Burgin playing his imaginary violin while teaching, 1960s.

Raphael Bronstein, who had been Burgin’s fellow student in Auer’s class at the Conservatory, recalled in his memoir of Burgin going to him at that time for help in playing Bach: “Auer always demanded his pupils play Bach after their first few lessons, but I had had no experience with that…I was asked to play the g minor Sonata and asked Richard for his help. He generously gave me my first true picture of Bach, with an analytical approach which has continued to influence my understanding of the composer’s greatness throughout my life.”[4] Raphael Bronstein, “Richard Burgin Remembered.” Quoted by Lisa Robertson in in her doctoral dissertation, Richard Burgin, Artist and Master Teacher, FSU School of Music, 1998.

Once Burgin came to the United States, he quickly established himself as one of the two most prominent violin teachers in Boston, the other being the Bohemian (Czech) virtuoso, Emanuel Ondricek (the teacher of Ruth Posselt). In addition to private pupils, including several of his BSO colleagues who took private lessons from him over the years, Burgin also held teaching positions at various institutions in the Boston area. In 1924 he joined the faculty of the New England Conservatory of Music where he remained until his retirement from the BSO, eventually becoming head of the string department and director of the orchestra there. He also taught at Wellesley College, Boston University, and the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood (from 1940 to 1963). From 1963 until the end of his life, teaching became his professional focus. In addition to his work as Professor of Music at Florida State University (1963-1972), during the summers Burgin served as master teacher, director, and/or conductor in various seminars, workshops, and string congresses in the United States and Canada: the National Youth Orchestra of Canada (1965); Co-director of Stetson Festival Institute at Daytona Beach and Director of the Institute Orchestra (1966); Director and Conductor of the orchestra of the Annual AFM Congress of Strings (Eastern Section) 1967-1970; 1968, May 26-31, Director, 5th annual Conducting Symposium for Young Experienced Conductors at FSU School of Music (1968); Director of string program and coaching staff at Stetson University’s Summer Institute (1972); co-director of International Conducting Symposium at Jacksonville University (1975); Master teacher at New College Music Festival, Sarasota Fl (1976-1980); and Leader of the String and String Conductors Workshops at Artsperience, Canadore College, North Bay, Ontario (1978)]

Teaching has advanced. It is better than it was. I am a great believer in the future. There have always been talented students, but today one can teach more in depth. Today [1977] you teach by explanation, not imitation. Yet, too much analysis can also ruin the performance of music.

I have been a teacher ever since I can remember and I have some very particular ideas on the education of a musician. I am critical of what they call general education and the broad range of subject requirements for music students in most colleges. There is a prevalent feeling among music majors at universities that they cannot study what they really want—they don’t have the time. Therefore, I often argued at FSU faculty meetings about the so-called curriculum, if music students have to study a science, why can’t they study acoustics?

Our conception of teaching violin is of necessity split between teaching the ability of playing the instrument, and the musical value of the music one plays. We must not forget that the violin is an instrument that requires a very early age to begin practice. It’s a very delicate instrument and usually those who are successful at playing it, whether as a soloist or in any other capacity, those who are really outstanding musicians, they all started very, very young, from maybe four to eight years old, seldom later. There are exceptions, and very successful ones, and they are very proud of the fact that they did not start so early, they even brag about it, and rightly so. But ninety-nine percent of successful violinists started very early.

At the age of five or six all one can do is develop the ability, the physiological aspect of handling and mastering an instrument, and that is completely natural because a child can not comprehend anything else about violin playing. And so, teachers focus on that. With a gifted child, you can make extraordinary progress. But then comes a turning point, usually around the age of twelve or thirteen, which has a big effect on the future, and teachers really cannot do anything about that. That’s probably the point when, as Auer used to say, some get better and others get worse.

I personally do not think that technical mastery of the instrument is all-important. It is conceivable that one can master the violin to such a point that technical mastery itself becomes ideal and can even give great satisfaction to the listener. But it is still the application of one’s mastery towards expressing what one feels in the music that is decisive. Artistry still has to be related to musical thought, the musical composition itself and other intangibles that go beyond just playing the notes beautifully, in time and in tune. There is something—it’s very hard to put your finger on what it is—there is something beyond technical mastery, and everybody will agree there is. The very fact that some compositions can last for so many years and still be enjoyed and others can not, proves that there is quite a difference between a work of one composer or another or even between two different works by the same composer, both technically irreproachable. The instrumentalist has to develop with the music he performs. If he only stays at the height of technical efficiency and ability, then sooner or later, he will not satisfy a great number of people, no matter how well he plays.

Talent, I think, is determined by the ear, not in the sense of pitch only, but by sensitivity to beauty of sound. I think that a genius like Heifetz did not just have an ear for music, or perfect pitch, he had an ear sensitive to the quality of sound, an ear sensitive to resonance. And he would never be satisfied until he reached the point that satisfied his ear. The tragedy is that the moment such a musician satisfies his ear, his ear gets better, and so he’s never happy, really. It’s the tragedy of genius, the moment he comes close to his ideal, it eludes him and he has to work harder.

My personal experience and private conversations with talents of this caliber is that they are never really quite happy. No matter how well a great artist performs his or her part, I have seldom encountered one who is totally happy. Well, they are happy that they had a success, that they were appreciated, but in terms of inner happiness, they never think that they have really achieved all they wanted. There’s always something that they would like to have done still better. On the other hand, I’ve found with lesser talents, that very often they are quite satisfied and happy even if they come not quite to what they hoped to, but very close. That has been my experience: that the great artists never stop working, really are always unhappy and in great need of focusing on something else, to get away from what their real aim is.

There is one thing which has been somewhat neglected in our teaching of single voice instruments, that is, every orchestral instrument. Our music has harmonic progressions or implied harmonic progressions, it has polyphony and counterpoint. And the moment you have polyphony and counterpoint, or even poly-rhythms, an instrumentalist on a single voice instrument cannot be considered a soloist in the literal sense of the word because one voice cannot perform the music alone. The moment one player can’t play alone, he has to play with at least one more person, and that means there’s bound to be a certain give and take in the performance of music.

Unfortunately, that is something that has not been sufficiently impressed upon all the young talents who often achieve great virtuosity in the mastering of their instruments. They are sometimes not even aware that others are also participating and that unless they play music which is written only for their instrument—and that is perhaps no more than one-and-a-half percent of the whole music literature—they are not performing solo. They may be performing a very important part, but they are not performing that part alone. It is probably better nowadays [1970s] because of the technical means that are available for listening to get the general idea of a piece, like recordings and so forth.

That was not the case in my early youth because we did not have those means of acquainting ourselves with the entire work—we could hear it only when we had the opportunity to attend a live performance. So we had to prepare by ear, train our ears so that when we’d look at the score, we could at least imagine what was going on.

I once conducted an informal survey among my colleagues, not so long ago. I remember speaking to an excellent young viola player who is also a teacher and I asked him, “When did you first get interested in playing the Bartok Concerto for Viola?” He said it was when he was still young. “Well,” I continued, “was it suggested by your teacher or did you hear it and want to play it or did you hear of it, or how did it happen?” He replied that he happened to have heard it on a tape, performed by a well-known artist. “And what was your reaction?” I asked. He said, “I thought I’d like to study it and try my ability on it.” “And what did you do then?” “Well, I got the music,” he said, “and I spoke to my teacher and told him I’d like to study it.” I said, “When you bought the music, what did you do first?” “Well,” he said, “I took my part and found the passages that I thought would be difficult and started to practice them.”

That one case seemed to me characteristic. And it is similar to an actor who wants to learn the role of the lead in a play getting a copy of just his lines and learning them irrespective of whether they are part of a dialog or what their context is, or what brings his lines about. That would be inconceivable. But it happens all the time with players of single voice instruments in music. If you want to understand a piece of music, especially a complicated work, even listening to a recording of the whole piece several times isn’t enough, you really need to find out how the composition is constructed and that means—studying the score. And that is somewhat neglected in musical education, even now.

By not having a serious look at the score to begin with, the instrumentalist is liable to waste an enormous amount of time because he is likely to discover that what he thought was so extremely important to bring out, turns out to be of very little consequence as far as the totality of the composition is concerned. What the soloist thought was so important in his part may not even fit in at all well with the work as a whole even to the point where, when a major work is performed of symphonic proportions, the player of the so-called solo part, the star performer, is not at all concerned with what is going on and he can actually be in contradiction sometimes with all the other people on stage. Correcting this sort of soloist’s tunnel vision is somewhat neglected by teachers.

Now I know that many teachers say that a student can listen to a recording and find out about the whole work that way, but that is a dangerous approach because he will be listening to preconceived opinions and he has to accept them because he hasn’t formed an opinion of his own. I think it would be much better if he would, to the best of his ability, study what the score says and then compare it with an experienced performer (or group) to see to what degree he was on the right track or wrong track. He might even decide that the recording is wrong and he is right! I wouldn’t mind that either.

Styles of playing certain works have become standardized to such a degree, even “mistakes” have been standardized, that one sometimes wishes one’s students would, regardless of the standard, have their own ideas and articulate them. If they do so successfully the result would probably be much more convincing than just imitating their favorite. I think there’s a Latin proverb to the effect that when two people say the same thing, it is not necessarily the same. So, imitation at best is still a copy, not the same thing. Of course, the really gifted players realize that and get out of it and they do project their own originality. However, the great majority of so-called “talented players” certainly play beautifully, for the most part, but in their “beautiful playing,” there is nothing of their own at all. In fact, their way of projecting what is a good imitation may be an imitation not necessarily of one, but of two or three different players.

I suppose my criticism in this case is to a certain extent a criticism of teaching, in cases where teachers do not encourage originality in their students. Of course, I can understand that approach because encouraging originality goes against the very nature of teaching whenever teaching means inculcating in the student the teacher’s experience and the teacher’s feeling.

And that is why I think that fingering a piece for an advanced student is completely wrong, not because the fingering is wrong—it is probably correct—but because it really trains a gifted young musician to be an eternal student. The teacher who does that fails to convey to students some very important things if not about music, then about life: namely, that as a rule, pupils are younger than teachers, that besides the works the pupil is playing now, he may be playing newer works ten years from now and then, still newer works. The main fact about an advanced student is that he is at the point of development where he does not need the teacher anymore. That should be the teacher’s aim, his hope; just like a father wants his child to grow up to the point where he won’t need a father anymore. And vice versa: the student’s aim should be to get rid of his teacher as soon as he possibly can without doing himself any harm, and stand on his own feet. And the mutual striving to separate from each other will make a really wonderful student-teacher relationship.

For five years I was at the New School in Sarasota, Florida where Joe Silverstein had a master class and invited me to come. In one of those classes, after students had played and he commented, one of the younger students, very gifted, asked me a question. Because I’d had such a long career and remembered artists who achieved great fame who they knew about but had never heard, they asked me, if I thought that the general quality of playing and studying now had deteriorated or improved or was about the same as it was in my time, three generations ago? And I thought about it and said that I honestly thought it had improved.

Burgin at Master Class in New School, Sarasota, summer 1977.

It’s amazing what has been accomplished nowadays (mid-1970s). I don’t know whether the improvement is due to better teaching, but the general way of making music, the methods of communication available has led to improvement because nowadays, we can listen to each other more—then, you had to go to a concert to hear a piece, now you can listen to it in several different performances, without leaving the house. Music has become much more accessible.

To give an example of how slowly and imperfectly one sometimes came to know certain things back in my youth, I recall that when I first got acquainted with the Kreutzer Sonata by Beethoven, I knew it as a piece for two violins because my teacher then was Lotto who played everything on the violin, including all accompaniments. And you didn’t miss much from his violin accompaniment. But because I had no way of easily hearing it otherwise, I really thought that it was a piece for two violins because that’s how I played it with Lotto when I was a boy. I never suspected there was a piano part in that piece.

The first time I heard the Kreutzer Sonata played as it is written was two or three years later, in the summer, out of town. I happened to come into a house where a violinist and pianist were practicing after I heard the music, recognized it but could not believe a violinist and pianist were playing it! It impressed me enormously because I was crazy about that piece. Even for two violins, I was crazy about it. It was a new world.

I believe that the best way to approach the study of a work that is new for you is not to listen to a recording of it, but to study the score in its entirety, just the way an actor has to get acquainted with the whole play before he learns his lines. The actor has to know at least who is talking to him. He may be the star of the show but he still needs others to communicate with—without the rest of the play, he is nothing. He can not always have soliloquies, be Hamlet all the time, philosophizing to himself. When you are playing with others you not only have to react, you have to know who you are reacting to.